Climate change poses a common and potentially overwhelming

macrofinancial risk for all SEACEN member countries.

Michael D. Patra, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India, 15 February 2024

Introduction

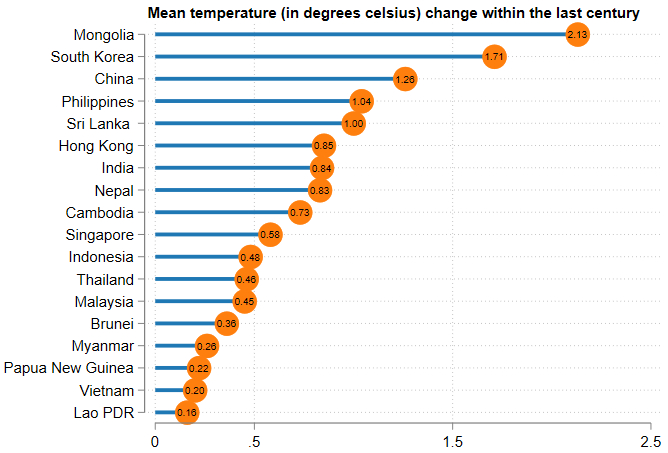

Many SEACEN economies are acutely vulnerable to natural disasters and the broader impact of climate change. Figure 1 illustrates the mean temperature and precipitation change within the last century for all but one of the SEACEN member economies. All have experienced an increase in mean temperature (top panel), ranging from 0.2 to 2.1 degrees centigrade, and most have seen a rise in mean precipitation (bottom panel).

Figure 1: Temperature and precipitation change in SEACEN member economies

Data source: Haver, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Indicators.

The challenges generated by climate change can manifest in several critical ways:

- Global surface temperatures are rising noticeably and the scale of aridification is increasing, triggering a shift in temperature zones. Such changes significantly affect agricultural production, a cornerstone of many SEACEN economies, by altering growing seasons and crop viability. In addition, there is an observed rise in the scale and frequency of extreme weather events, including droughts, heavy precipitation, snowfall and tropical storms. These phenomena not only damage infrastructure and affect livelihoods but also strain resources and emergency response capabilities.

- The warming of the world’s oceans, paired with the attendant rise in sea levels, poses another grave threat, which is the potential to fuel more frequent and more potent storms, exacerbating the challenges faced by these economies. Beyond the immediate impact on weather patterns and agricultural productivity, climate change is contributing to a significant loss of species or biodiversity. This loss threatens ecosystems and the services they provide, further jeopardising food security, water sources and livelihoods.

- The health risks associated with climate change are profound and multifaceted, ranging from the increased prevalence of heat-related illnesses to the spread of vector-borne diseases, which can have dire consequences for public health systems.

- Finally, the economic and social fabric of SEACEN member economies is under threat from the poverty and displacement that result from climate change. As natural disasters and climate change erode the means of subsistence for many, there is an increasing risk of displacement, both within countries and across borders, leading to heightened vulnerability and instability.

This confluence of challenges underscores the urgent need for concerted action and collaboration to mitigate the impacts of climate change and bolster resilience among SEACEN economies. As a result, some SEACEN member central banks/monetary authorities have started to incorporate climate change into their central banking framework. Others have yet to embark on this journey.

It is worth pointing out that the concept of climate change often invokes the ‘tragedy of the commons’, where individual actions lead to the depletion of a shared resource. Typically, the responsibility to tackle such a collective issue falls predominantly on the public sector, which possesses the authority to implement policies and regulations aimed at environmental conservation and sustainable practices, including the power to tax carbon-intensive sectors and industries. But the risks posed by climate change extend far beyond environmental degradation, as its effects can strike at the very heart or fabric of our economies. This intersection where ecological issues meet economic welfare impacts both monetary and financial stability, and places climate change within the realm of central bank concerns and priorities. While central banks do not have direct control over environmental policies, they must remain acutely aware of the risks posed by climate change to the economic and financial system. As such, the latter has been likened to a new type of systemic risk (Pereira da Silva (2023)). An awareness of what the central bank can do in terms of meeting the challenges of climate change and what it cannot do is vital in this regard. Finally, and strictly within the limits of its remit, a central bank can always stand ready to advise and support, if appropriate, the government with complementary climate-related policies.

This blog sets out some organising principles for central banks just starting to incorporate climate change into their framework. It highlights some critical steps and strategies that central banks can adopt to address and mitigate the impact of climate change, underscoring their evolving role in navigating this global challenge.

More specifically, we suggest a basic four-pronged approach, consisting of:

- Ways to prioritise climate risks through a clear taxonomy;

- Conducting a preliminary analysis of the most pertinent climate risks and their likely impact on price and financial stability concerns of the central banks;

- Understanding the relevant data sources and modelling issues; and, based on the above three points,

- Deciding on the subsequent allocation and upskilling of central bank resources, including manpower resources, as well as strategically (re-)organising the central bank to optimally focus on addressing climate change.

Part I: Understanding the ‘green’ taxonomy

The basic − yet crucial − step for central banks to effectively integrate climate-related issues into their operational framework involves a meticulous process of assessment and strategy formulation. This critical first phase lays the groundwork for a comprehensive approach that positions climate considerations within central banking practices. The initiation of this process, inherently analytical in nature, prioritises the establishment of a broad understanding and scope that involves the development of a detailed taxonomy. Such a taxonomy serves as a foundational tool for categorising and defining green and sustainable financial activities with precision. By establishing a common language and a set of criteria for what constitutes ‘green’ and ‘sustainable’, central banks can more effectively identify and prioritise their interventions in the financial system. This taxonomy not only facilitates the differentiation between various types of green investments and activities but also helps map out the landscape of climate-related financial products and services.

The first part also involves a thorough identification of the country-specific causes of climate change, including the sources and types of emissions contributing to global warming and the specific physical impacts of climate change experienced within a country. This granular understanding is essential for tailoring the central bank’s approach to the unique environmental challenges and economic realities of its jurisdiction. By accurately identifying and categorising these elements, central banks can better assess the vulnerabilities and opportunities within their economies, directing resources and policies toward areas where they can achieve the most significant impact. Moreover, such a taxonomy enables central banks and financial institutions to understand and communicate the broader economic and human welfare implications of climate change. By linking environmental changes to economic outcomes, central banks can articulate the necessity for urgent action and investment in green and sustainable practices.

The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) stands out as a leading example in this endeavour, working towards the development of a green taxonomy tailored for central banks. The NGFS’ efforts in building a green taxonomy are instrumental in guiding central banks and financial institutions worldwide in aligning their operations with environmental sustainability goals. This collaborative effort underscores the importance of a shared framework and common standards in the global fight against climate change, facilitating a unified and effective response from the financial sector.

The taxonomy typically categorises risks into three main types: transition risks, physical risks and legal or liability risks. Each of these risk categories has distinct characteristics and implications for economic, monetary and financial stability, necessitating targeted approaches for their assessment and mitigation.

Transition risks

Transition risks arise from the process of adjusting to a low-carbon economy. These risks are associated with policy changes, technological advancements and shifts in market preferences towards more sustainable practices and products. As economies move away from fossil fuels and other high-carbon industries, assets in these sectors may lose value rapidly, leading to stranded assets. This devaluation can affect lenders, investors and insurers who have exposure to such assets, potentially leading to significant financial losses. Moreover, transition risks also encompass the costs of adjusting to new regulations, such as carbon pricing mechanisms, emissions standards and energy efficiency requirements. Companies and industries that fail to adapt to these changes may face increased operational costs, reduced competitiveness and declining profitability, which can have knock-on effects on the financial sector through loan defaults, investment losses and decreased asset values.

Physical risks

Physical risks are directly related to the impact of climate-related natural disasters and long-term changes in climate patterns. These include extreme weather events like hurricanes, floods, wildfires, heatwaves and droughts, as well as more gradual changes such as rising sea levels and shifting agricultural zones. Physical risks can lead to direct financial losses for businesses and households through damage to property, infrastructure and agricultural land. The repercussions of physical risks on financial stability are multifaceted. Insurers may face increased claims, potentially leading to higher premia or the withdrawal of insurance coverage for high-risk areas. Banks and financial institutions could see a rise in non-performing loans as borrowers struggle to cope with the aftermath of disasters. Moreover, the broader economic impacts of these events, such as reduced productivity and economic displacement, can lead to decreased economic growth and financial market volatility.

Legal or liability risks

Legal or liability risks stem from the potential for parties affected by climate change to seek compensation from those they hold responsible. This can include litigation against companies for failing to mitigate their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, not adapting to climate change impacts, or not adequately disclosing their climate-related risks to investors. Legal risks can also arise from non-compliance with emerging regulations and standards related to climate change and environmental sustainability.

These risks can have significant financial implications for businesses and, by extension, the financial institutions that underwrite, lend to, or invest in them. Legal proceedings can result in substantial costs, both from legal defences and potential compensation payments, as well as damage to reputation and investor confidence. For the financial sector, this can translate into asset devaluation, increased credit risk and broader market instability.

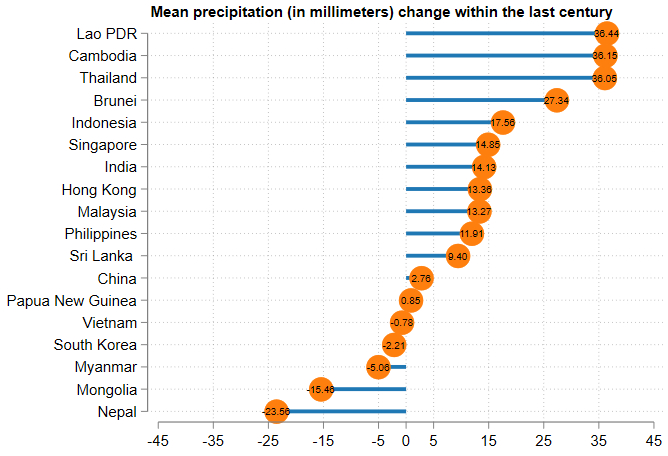

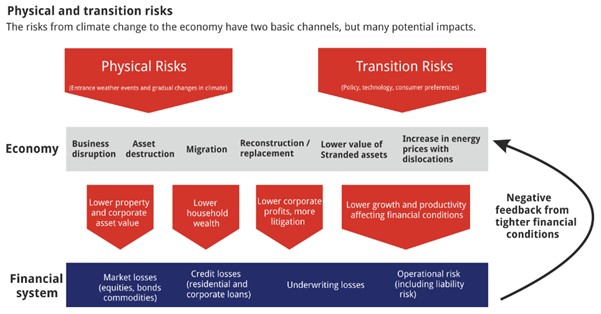

Figure 2 illustrates in more detail the various transmission channels through which physical and transition-related risks can affect the economy and then financial stability.

Figure 2: Risks emanating from climate change

Source: IMF (2019, p. 26).

As can be seen, each of three risks highlighted carries its own set of implications for economic stability and policymaking.

Impact through physical risks

- Physical risks can severely disrupt supply chains, leading to scarcity of materials, increased production costs and, ultimately, rising consumer prices. Such dynamics pose a substantial challenge to central banks, as they may lead to inflationary pressures that conflict with mandates to maintain price stability. The task of accurately forecasting inflation becomes more complicated in the face of these unpredictable and increasingly common events.

- Furthermore, extreme weather events can wreak havoc on physical and infrastructure capital, which are critical components of economic growth. The destruction of roads, bridges, factories and homes not only requires significant investment to rebuild, but also temporarily, if not permanently, reduces the productive capacity of the economy. This reduction in capacity can lead to decreased economic output and growth.

- Mass immigration or displacement of the labour force represents another channel through which physical risks affect the economy. Large-scale movements of populations away from affected areas can lead to labour shortages in those regions, disrupting local economies and potentially leading to productivity losses. For central banks, managing the economic fallout from such disruptions involves complex assessments of labour market dynamics.

Impact through transition risks

- Adapting to a low-carbon economy is essential for long-term sustainability, yet it can also lead to economic and financial instability in the short to medium term. One of the primary challenges for central banks is managing the potential devaluation of carbon-intensive assets, resulting in stranded assets. As policies and market preferences shift towards greener alternatives, assets related to fossil fuels and other high-emission industries may lose value rapidly, posing risks to financial institutions and investors with significant exposures to these sectors.

- Moreover, the transition to a green economy requires substantial investment in new technologies, infrastructure and workforce re-skilling. Financing this transition poses a significant challenge, potentially leading to volatility in financial markets as capital is reallocated from traditional energy sectors to emerging green technologies. Central banks must navigate these dynamics, ensuring financial stability while also supporting the broader transition through monetary policy and regulatory measures (Mohan (2023)).

- Additionally, the transition process may be accompanied by social and economic adjustments as industries and workers adapt to new technologies and market demands. Central banks may need to consider the impacts of these adjustments on employment, income inequality and overall economic growth as they formulate monetary policy.

Part III: Data sources and modelling challenges

The novel nature of climate-change shocks, their wider transmission and the ultimate impact on the economy and the financial system is accompanied by the need for new data sources and modelling challenges.

Granular and innovative data sources

The intersection of economics and finance with climate change is increasingly becoming a focal point for researchers, policymakers, and financial institutions worldwide. As our understanding of climate-related risks and their implications for financial stability deepens, the demand for more granular data has surged. First and foremost, the importance of granular data in assessing banks’ exposures to climate-related risks cannot be overstated, particularly in climate stress testing. For example, information on banks’ exposures to companies and households, stratified by geographical factors such as whether the latter is located on a flood plain, is crucial. In addition, understanding the carbon footprint of financial institutions’ portfolios, including bank loans, offers insight into their indirect environmental role and impact. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Climate Change Indicators Dashboard (CID) provides a carbon footprint of bank loans (CFBL) indicator for 41 countries, facilitating cross-country comparisons, albeit at an aggregated sector level (IMF (2021)).

Emerging research further enhances our understanding of climate-related financial risks by incorporating analyses from both physical and transition perspectives. For instance, studies that leverage textual analysis from diverse sources, including newspapers and social media platforms like Twitter, offer fresh lenses through which to gauge public sentiment and awareness around climate risks. These insights have the potential to influence financial markets and institutions. Moreover, the application of Geographical Information System (GIS) science presents a promising frontier for dissecting climate-change risks in the financial sector. Aurouet et al. (2023) highlight how GIS can provide precise data on the location of physical hazards, aiding in the construction of derived indicators for deeper analysis. If central banks have not already done so, they can develop internal capabilities for processing and utilising GIS data, thereby enhancing their assessment of climate-related risks. This capability is particularly useful in the conduct of climate stress testing.

Lastly, the development or enhancement of environmental-economic accounting systems is imperative for countries to integrate economic and environmental data effectively. This integration is vital for a holistic view of the interplay between the economy and the environment. Noteworthy initiatives, such as the collaboration between Eurostat, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the IMF, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), have made significant progress in this direction. They have developed estimates of quarterly GHG emissions by industry and households, tracing back to the first quarter of 2010. Such high-frequency data can be invaluable for countries to monitor their progress toward climate goals, particularly within the 2015 Paris Agreement (Astolfi et al. (2023)).

Modelling issues

A diverse array of modelling approaches has been developed by both academics and practitioners, including banks and supervisors, to assess and understand climate-related risks in the economy at large and specifically within the financial sector. Each of these methodologies presents its unique set of advantages and challenges, contributing distinctively to our comprehension and management of the economic and financial risks posed by climate change.

A significant strand of this research leverages macro-econometric models which, by design, have a macro-level focus and offer valuable insights across varying time horizons. These models are primarily estimated based on historical data, providing a useful framework for understanding short to medium trends, as well as long-term and potential future scenarios. But their inherent limitation lies in the exclusion of micro-level analysis, which could offer deeper, more nuanced insights into individual and localised climate risks (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2021)). Further advancements in macroeconomic modelling have integrated concepts from stock-flow consistent models and complexity science (such as agent-based models), providing new perspectives on how economic agents interact and how shocks can propagate through different channels. These models highlight the importance of understanding feedback loops, non-linear dynamics and the potential for tipping points in the climate-finance nexus.

Moreover, the interplay between climate change and financial systems is increasingly being examined through the lens of network science. This approach offers insights into the interconnectedness of various sectors and agents, elucidating how risks can cascade through networks, potentially leading to amplified and widespread impacts (Monasterolo (2020)). While these innovative modelling techniques offer substantial contributions to our understanding, they are not without their drawbacks. For instance, agent-based models and network models demand significant computational resources and detailed data, which can sometimes lead to opaque results and challenges in interpreting diverse outcomes across different simulations (BCBS (2021)).

In addition to these approaches, the application of machine learning (ML) techniques in climate-change research represents a promising frontier. Traditionally used for prediction, ML methods are now being harnessed to enhance causal inference from observational data, albeit with a primary focus on short-term effects. This burgeoning field offers valuable tools for controlling numerous covariates in high-dimensional settings, thus improving the robustness and depth of climate-related risk analysis (Abrell et al. (2022)). Lastly, the utilisation of dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models, particularly the environmental DSGE (E-DSGE) variants, provides a structured approach to analysing environmental policies and their economic impacts. Despite their widespread application, these models face criticism regarding their sensitivity to specific assumptions and the challenge of accurately modelling the nuanced effects of climate change on welfare and production efficiency (European Central Bank (2021)).

Summing up, the diverse landscape of modelling approaches enriches our understanding of the economic and financial implications of climate change, offering a toolkit for policymakers, researchers, and financial institutions to navigate this complex domain. While each model has its strengths and weaknesses, the collective insights they provide argue for the development or enhancement of a suite of models, which central banks are currently undertaking in their regular modelling work.

Part IV: Re-allocation of resources and upskilling in central banks

Given the varied nature of climate change and its implications for both monetary and financial stability, a central bank cannot deal with all these possibilities at the same time. As such, a resource-constrained central bank will have to be re-organised internally to tackle climate change optimally across the institution. To effectively address and navigate the complexities of climate change, central banks can prioritise the training and skill development of their staff in several critical areas. This initiative should encompass specialised training in climate economics, climate scenarios, sustainable finance, modelling the effects of climate change and risk assessment to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted impacts of climate change on the economy and financial systems.

As discussed in Part II, central bank employees need a deep understanding of climate economics to grasp how climate change influences economic growth, inflation and financial stability. This knowledge is essential for making informed policy decisions that consider the long-term economic implications of environmental changes. In addition, training in sustainable finance is crucial for central bank staff. It should cover topics such as sustainable investment practices, green bonds and other financial instruments aligned with environmental goals, enabling the integration of environmental considerations into financial and investment strategies. Moreover, understanding how to assess climate-related risks is fundamental. This includes analysing both physical risks, such as the impact of extreme weather events on assets, and transition risks, which involve the economic effects of policy changes aimed at mitigating climate change. Equipping staff with the skills to evaluate these risks is essential for the development of robust risk management frameworks that can withstand the challenges posed by climate change.

Beyond individual training, central banks can foster collaboration with climate experts, academia, international organisations and other central banks. Engaging in interdisciplinary dialogue and research partnerships enriches a central bank’s understanding of climate issues from multiple perspectives, ensuring a holistic approach to policy formulation and risk assessment. This collaborative stance supports the central bank in crafting well-informed, effective strategies to address the complex challenges climate change presents. Furthermore, establishing dedicated full-time climate teams within central banks to conduct in-house research on climate change is critical. These teams can offer invaluable insights into the impact of climate-related risks on monetary policy, financial stability and the broader economy. By leveraging data analytics, these teams can track and analyse climate trends, emissions and their effects, providing a solid evidence base for policy decisions.

Climate literacy should extend across all departments of the central bank, not just among economists. Legal, risk management and communication departments, among others, should also possess a firm understanding of climate-related issues. This ensures that the entire organisation is prepared to address climate risks comprehensively and communicate these risks effectively to policymakers, financial institutions and the public.

Conclusion

The ten countries identified by the Swiss Re Institute (2024) as most exposed to the four weather perils of floods, tropical cyclones, winter storms (in Europe) and severe convective storms include five SEACEN member economies, underscoring the fact that climate change is a risk for all SEACEN member countries. It is undeniable that climate change impacts both core mandates of central banks, namely price and financial stability. But addressing climate risks involves concepts, ideas and challenges new to central bankers, representing a potential barrier to incorporating this issue into the central bank policy framework. We note that the absence of a ‘silver bullet’ to address climate-change risks makes co-ordination between the central bank and other stakeholders, such as the government, other public agencies, the private sector and other actors in society, both locally and globally, imperative.

In order to provide a roadmap on the way ahead, we suggest a four-pronged approach as the organising principle for central banks setting out on the climate-change journey. We hope that we can facilitate planning in terms of directing central banks towards meeting this common and potentially overwhelming risk. The approach starts with the development of a green taxonomy. The second part is the identification of country-specific causes of climate change and the specific physical manifestations of climate change on monetary and financial stability. A range of issues have been found to significantly impact the macroeconomy through various transmission channels, including the physical risks associated with the increased severity and frequency of extreme weather events, as well as the transition risks involved in moving towards a low-carbon economy. Each of these areas of risk carries its own set of implications for economic stability and policymaking. The third part addresses the associated data and modelling issues. Not only is it highly likely that the transmission mechanisms are non-linear, depending on potentially irreversible climate ‘tipping points’, but also include equally complex feedback effects. This puts approaches to modelling these transmission mechanisms at the frontier of what is currently available, both in terms of theory and empirical implementation. In addition, modelling the effects of climate change on monetary and financial stability requires new and innovative data sources, which may not – yet – be available in various jurisdictions. The fourth and final part suggests a re-allocation of resources within the central bank and an upskilling of staff to meet the profound challenges presented by climate change.