The Great Financial Crisis (GFC), which began in 2007 and whose effects persisted for a decade, spurred a cavalcade of major worldwide regulatory, supervisory, and resolution reforms for the banking sector and the broader financial sector. In particular, the massive costs incurred by resolution and deposit insurance authorities (and ultimately, taxpayers) to clean up failed banks prompted a renewed focus on bank resolution, particularly on the resolution of larger banks, with the aim of reducing the negative impact of a failed bank on financial stability and the real economy and requiring creditors of banks to bear a larger share of the cleaning-up losses.

One of the tools developed to push loss-bearing onto creditors of banks is “bail-in,” the practice of either writing down liabilities to creditors directly or converting these liabilities to bank equity. Bail-in had existed before the GFC but was not fully articulated until the European Union (EU) adopted the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) in 2014. Worldwide, using their own traditions and practices and adapting suitable portions of the BRRD, other jurisdictions followed suit and began instituting bail-in more formally for senior debt and for liabilities qualifying as Additional Tier 1 (AT1) and Tier 2 (T2) capital. (For a more detailed discussion, see The SEACEN Centre’s SEACEN Policy Analysis Series Issue #2 on “Bail-in: a Primer” from May 2020.)

Since the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s, bank failures have been a relatively uncommon feature of the financial sector landscape in the SEACEN stakeholder space. And Asian banking sectors, so far, seem to have weathered the COVID-19 storm quite well. But the horizon for the remainder of 2021 and on into 2022 is clouded with uncertainty about the future trajectory of the pandemic, the responses of governments, firms and households to this trajectory, and the intrinsic (as opposed to reported) asset quality of banks. Accordingly, jurisdictions are focusing intensively on their recovery and resolution regimes. To find out how ready SEACEN stakeholder jurisdictions are to carry out bail-in, in the event of costly or widespread bank failures, The SEACEN Centre undertook a survey of its stakeholders in 2020. The purpose of this blog post is to report the findings of this survey.

Summary of main survey findings

The survey findings show that SEACEN stakeholder jurisdictions, as a whole, have a way to go in fully developing and implementing their recovery and resolution regimes, including the possibility of bail-in. Some of the more interesting findings include the following:

- Most jurisdictions require at least a subset of banks to have recovery plans.

- Most jurisdictions have triggers, objective or subjective, that would require a bank to activate its recovery plan.

- About half of jurisdictions that require recovery plans allow bail-in to be included as a strategy in those plans.

- Fewer than half of jurisdictions, however, include bail-in as a possible resolution tool.

- Also, and even more surprisingly, fewer than half of jurisdictions have triggers that would require a bank to be placed in resolution.

- Although bail-in is authorised in some jurisdictions as a recovery plan strategy or resolution tool, it has not been used anywhere in at least the last ten years.

- Also surprising is the fact that nearly half of jurisdictions have some requirement (analogous to the EU’s Minimum Requirement for Own Funds and Eligible Liabilities or MREL) for a minimum amount of regulatory capital plus some additional liabilities – in other words, a requirement for a broader aggregate of capital and liability holders that could absorb losses before or during the resolution process.

- Fewer than half of the jurisdictions have a well-defined priority of claims on the assets of banks in resolution.

Detailed findings

The survey was designed to gain insights on the adoption of bail-in as a recovery and resolution tool in the SEACEN economies. The survey which was sent to the respective SEACEN member central banks and monetary authorities comprised ten questions on bail-in liabilities, recovery planning, and resolution planning.

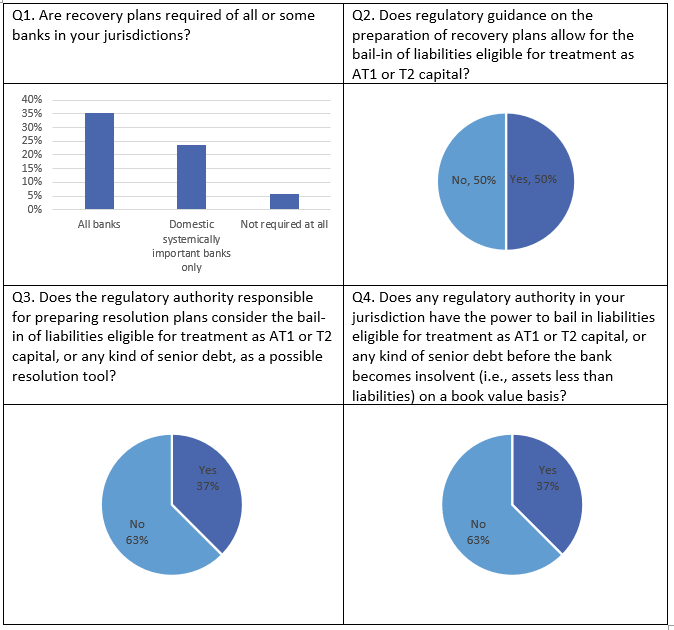

From the responses of the survey, it is found that the majority of the central banks and regulatory authorities require banks to have recovery plans in their jurisdictions. Out of the 17 survey respondents, only one regulatory authority does not require banks to have recovery plans and it also highlighted that there is no formal recovery regime in place (Q1). Thirty-five per cent of the respondents require all banks to have recovery plans and another 24 per cent require only domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBS) to have recovery plans. For the remaining respondents, banks that require recovery plans include the global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), and locally-incorporated banks which cover foreign bank subsidiaries, but excluding foreign bank branches.

While half of the respondents allow for the bail-in liabilities eligible for treatment as AT1 or T2 capital as part of the recovery plan (Q2), only 37 per cent consider the bail-in liabilities as a possible resolution tool (Q3). Thirty-seven per cent of the survey respondents also stated that the regulatory authorities in their jurisdictions have the power to bail in liabilities eligible for treatment as AT1 or T2 capital, or any kind of senior debt before the bank becomes insolvent on a book value basis (Q4). One respondent commented that while statutory bail-in powers are not in place in the jurisdiction, the prudential standards require that AT1 and T2 capital instruments have certain conversion or write-off terms included in them by way of contractual agreements. Another responding institution stated that the prevailing laws provide bail-in power to the authorities during the recovery process (through contractual bail-in) as well as the resolution process (through statutory bail-in). For contractual bail-in, such power lies in the stand-alone regulatory authority as a part of the recovery tools. For statutory bail-in, the power lies in the resolution authority and is only applicable upon declaration of a financial crisis by the President.

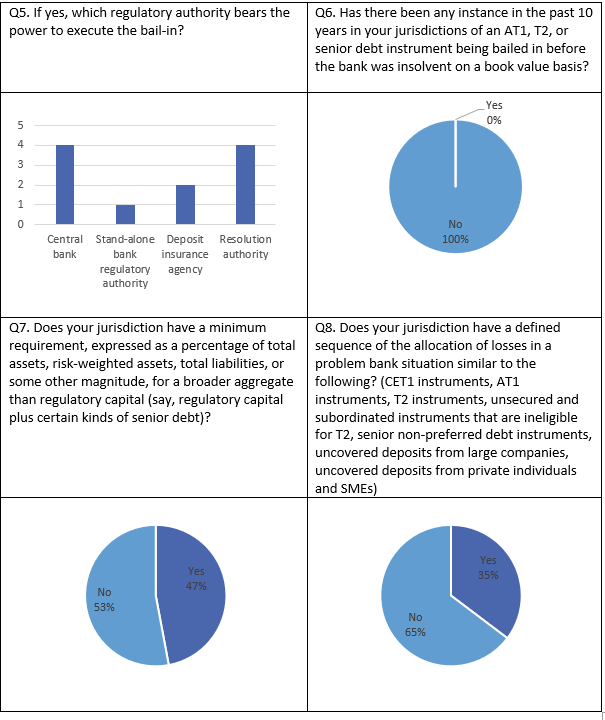

Of those jurisdictions which have bail-in authorised by law, four jurisdictions reported that the power to execute the bail-in is borne by the central bank. One reported that the power is borne by the stand-alone bank regulatory authority, two by the deposit insurance agency and four by the resolution authority. It is important to note that in most jurisdictions that responded yes to Q4, the central bank acts as the resolution authority as well. In another jurisdiction, it is the deposit insurance agency that functions as the resolution authority. Two jurisdictions commented that the power to execute the bail-in is jointly authorised by two institutions – the central bank and the deposit insurance agency; and, the stand-alone bank regulatory authority and the deposit insurance agency.

No jurisdictions have reported of any bail-in liabilities being used to bail-in insolvent banks on the book value basis (Q6) in the last ten years. This shows that the bailout option is still a more favourable option among the SEACEN economies as compared to the bail-in.

Almost half of the jurisdictions (47 per cent) have a minimum requirement, expressed as a percentage of total assets, risk-weighted assets, total liabilities, or some other magnitude, for a broader aggregate than regulatory capital (Q7). One of the institutions reported that it has imposed an additional loss-absorbing capacity requirement on the D-SIBs, but it is anticipated that the D-SIBs will satisfy the requirement predominantly with additional T2 capital. On the other hand, two institutions mentioned that the capital adequacy ratio is also supported by the leverage ratio. About 35 per cent of the survey respondents stated that their jurisdictions have a defined sequence of the allocation of losses in the following order: CET1 instruments, AT1 instruments, T2 instruments, unsecured and subordinated instruments that are ineligible for T2, senior non-preferred debt instruments, uncovered deposits from large companies, and uncovered deposits from private individuals and SMEs. This sequence is akin to the EU model. For the rest of the survey respondents, some mentioned that they have a different sequence for the allocation of losses from the above, while some highlighted that no defined sequence for the allocation of losses has been established, and is still under review. Further comments are shown in the following Box.

Box: Open responses to Q8 – “Does your jurisdiction have a defined sequence of the allocation of losses in a problem bank situation similar to the following? (CET1 instruments, AT1 instruments, T2 instruments, unsecured and subordinated instruments that are ineligible for T2, senior non-preferred debt instruments, uncovered deposits from large companies, uncovered deposits from private individuals and SMEs)”

- In the context of bail-in, no defined sequence has been established. In the winding up of a bank, the assets of the bank shall be available to meet all liabilities in respect of all deposits in [our jurisdiction] in priority over all other unsecured liabilities in [our jurisdiction] other than the preferential debts set out in subsection 527(1) of the Companies Act 2016 in the order set out in that subsection and debts due and claims owing to the Government under section 10 of the Government Proceedings Act 1956.

- In general, prevailing laws in [our jurisdiction] would ensure that shareholders’ equity is subject to losses first, and no loss will be imposed on the creditors holding senior debts until those holding subordinated debts have been fully exposed to losses. Moreover, all third-party deposits are on the same level of hierarchy of claim. In [our jurisdiction], the legal basis for creditor claim hierarchy is governed by the Code of Civil Law within articles concerning Bankruptcy and Suspension of Debt Payment Obligations (“Bankruptcy Law”). Under the aforementioned Laws, there are three (3) types of creditors:

- separatist creditors that have collateralised claim against debtor;

- preferred creditors that been given a preferred position by relevant civil law; and

- concurrent creditors without collateralised claim or preferred position against debtors.

- For the banking sector, the hierarchy of claim for banks’ creditors is also governed in Article 54 of the [redacted] Law. Under the aforementioned law, the allocation of losses in a problem bank on bank liquidation circumstance shall be exercised in the following hierarchy:

- refund of the advance payment made to the accrued and unpaid remuneration for staff;

- refund of the advance payment for the severance payment for the staff;

- judicial fees and charges at the court of law, cost of unpaid auction expenses, and cost of operational expenses;

- resolution cost incurred by the deposit insurance corporation and/or payments on insured deposit to be paid by the deposit insurance corporation;

- unpaid taxes;

- uninsured portion of deposits and ineligible deposits; and, other creditors.

- The central bank’s Basel-III regulations and the terms of AT1 and T2 capital instruments issued under these regulations contain the provisions regarding the sequence of the allocation of losses.

- While the allocation of losses would generally follow this sequence, it is not enshrined in legislation. Conversely, our jurisdiction has depositor preference, which dictates the priorities for application of assets in insolvency.

- A priority claim list is available in the Banking Act.

- No formal recovery regime in place.

- We are amending the regulation.

- In the absence of a formalised resolution framework, we are guided by existing legislations that would be used as reference. One such law is the Secured Transactions Order, 2016, which specifies the ranking and priority of creditors, as follows:

- secured/ preferential creditors;

- retail/ corporate depositors;

- unsecured creditors;

- subordinated debt holders;

- shareholders.

- CET1, AT1, T2, unsecured and subordinated instruments that are ineligible for T2, senior non-preferred debt instruments, uncovered deposits.

- The central bank is adopting Basel I and Risk Based Supervision. The target year for adopting Basel III is not determined yet. Local domestic banks should have more time to meet the required level of Basel III in our jurisdiction.

- We are studying the issuance of relevant laws or regulations related to the sequence of the allocation of losses.

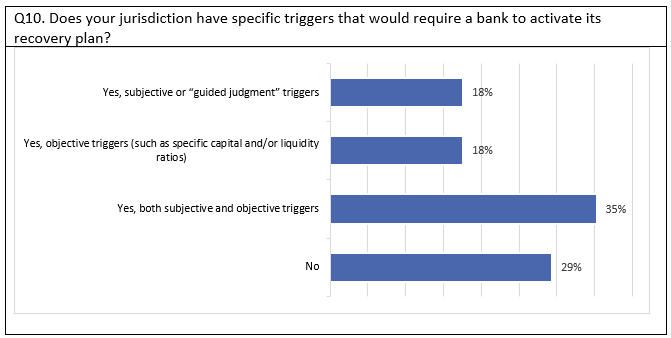

The majority of the survey respondents (71 per cent or 12 out of 17) stated that they have specific triggers that would require a bank to activate its recovery plan (Q10). Three jurisdictions mentioned that the triggers would be subjective or ‘’guided judgment”, while another three jurisdictions mentioned that triggers would be objective (for instance, specific capital and/or liquidity ratios). Six jurisdictions mentioned that the triggers would be both subjective and objective. One of the respondents commented that in its jurisdiction, banks have to decide on the triggers, and the selected triggers are subject to supervisory review.

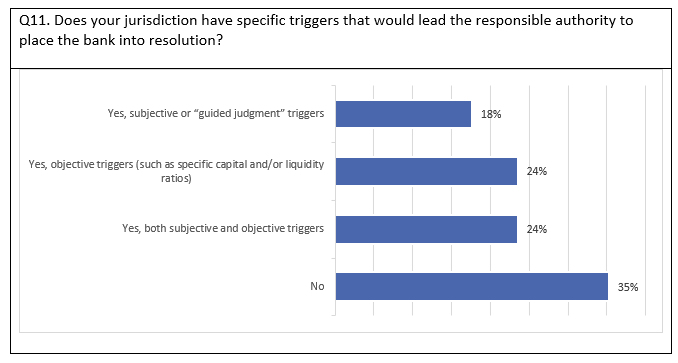

Sixty-five per cent of the responding institutions stated that their jurisdictions have specific triggers that would lead the responsible authority to place the problem bank into resolution (Q11). Out of those jurisdictions that have specific triggers to place banks into resolution, three of them use subjective triggers, four use objective triggers, while the rest use both subjective and objective triggers.

A respondent which answered ‘No’ for Q10 commented that while the regulatory authority’s resolution powers have specific triggers for use, the jurisdiction does not have specific legislated triggers for entry into resolution.

Conclusions

The bail-in tool, through which losses arising from the cleanup of failing or failed banks are imposed on liability holders rather than on the resolution authority or on taxpayers, is a relatively new and untested tool in recovery and resolution. Even in the EU, where it was institutionalised in a Directive with a mandate for its deployment under fairly clear circumstances and criteria, it has been used sparingly, mostly on smaller banks. Some policymakers, such as Neel Kashkari, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, have even argued that bail-in will hardly ever be used in the future because of the fears of financial sector authorities that a great many bank liabilities subject to bail-in will experience runs or sell-offs in the event of a prominent bail-in, due to the contagion effect.

It remains to be seen whether or not more SEACEN stakeholder jurisdictions will continue to develop and refine their resolution frameworks and include bail-in as a possible resolution tool, and for those that already have it, whether or not it will be used. There are already substantial AT1 and T2 liabilities issued by banks domiciled within the SEACEN stakeholder space, and some banks have also issued senior debt that could be bailed in. But so far, it seems to remain as a theoretical possibility rather than a fully-fleshed out strategy by Asian financial regulators.