The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS or the Basel Committee) has undertaken a lot of work on climate-related financial risks. This blog covers three themes from BCBS’ work on this topic:

- The focus on climate-related financial risks (and not the broader environment-, nature-, or ESG-related financial risks).

- Addressing climate-related financial risks within the existing Basel Framework.

- The 2023 review of the Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision, which includes climate-related financial risks as an integral part of banks’ risk management and supervisory practices.

Before we go into the details of climate-related financial risks, let us first highlight the role of the Basel Committee in the regulation and supervision of banks. The financial sector regulators and supervisors are familiar with Basel III, the global regulatory capital standard for banks. Like Basel III, the Basel Committee has published several standards and guidelines for the effective supervision of banks.

Background: What is the Basel Framework?

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS or the Basel Committee) is the primary global standard setter for the prudential regulation of banks. The Basel Committee has 45 members (consisting of central banks and supervisory authorities) from 28 jurisdictions, and eight observers including central banks, supervisory groups, international organisations and other bodies.

In order to fulfil its mandate of strengthening the regulation, supervision and practices of banks worldwide with the purpose of enhancing financial stability, the Basel Committee sets ‘Standards’, and issues ‘Guidelines’ and ‘Sound Practices’. BCBS also monitors and assesses the adoption and implementation of its standards in the member jurisdictions through the Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP) set up in 2012.

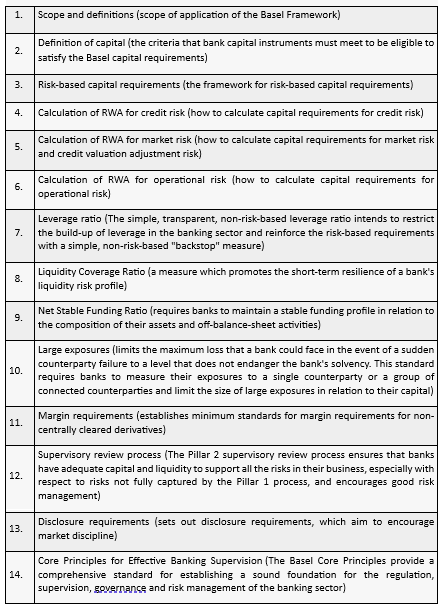

The Basel Framework is the full set of 14 standards of the BCBS, as shown in Table 1. The Standards cover all the areas of prudential regulation and supervision of banks and are expected to be fully implemented by the members of the Basel Committee (by virtue of their membership) and their internationally active banks. The BCBS Standards are minimum requirements and BCBS members may decide to go beyond them.

The BCBS Guidelines elaborate and supplement the standards in certain areas by providing additional guidance for implementation purposes. The Sound Practices generally describe actual observed practices, with the goal of promoting common understanding and improving supervisory or banking practices. BCBS members are encouraged to compare these practices with those applied by themselves and their supervised institutions to identify potential areas for improvement.

The Basel Committee publishes several documents relating to the implementation of its standards, such as The implementation reports to the G20; QIS Monitoring; surveys on subjects of supervisory interest; G-SIBs-assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement; countercyclical capital buffer; etc.

The BCBS publishes newsletters to provide greater detail on internal discussions within the BCBS. The newsletters provide information that may be useful for both supervisors and banks in their day-to-day activities. The newsletters are for informational purposes only and do not constitute new supervisory guidance or expectations, e.g., Newsletter on Covid-19 related credit risk issues.

The Basel Committee’s Work on Climate-related Financial Risks

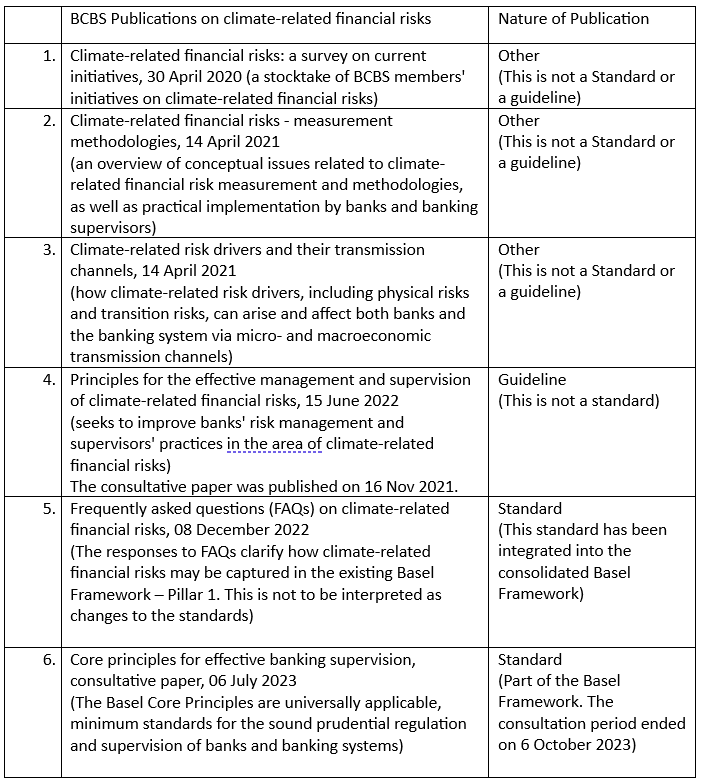

There is much debate about how best to reflect climate-related financial risks within the banking prudential framework. Recognising this need, the Basel Committee has come up with several publications on climate-related financial risks and their nature, i.e., whether these are a Standard or a Guideline or none of these two (Table 2).

In the remaining part of the blog, we discuss some of the key elements that are covered in the various publications of the Basel Committee.

1. The focus on climate-related financial risks (and not the broader environment-, nature-, or ESG-related financial risks)

As would be expected, BCBS focuses on ‘climate-related financial risks’, and not on the broader ‘climate risks’, which are not within its remit, have a much wider connotation and include the non-financial aspects of climate risk, e.g., the risk to human health and well-being due to an isolated case of a heatwave, which might not have an impact on the financials of banks. For this reason, the Basel Committee’s publications always use the expression, ‘climate-related financial risks‘, which it defines as, ‘The potential risks that may arise from climate change or from efforts to mitigate climate change, their related impacts and their economic and financial consequences’. The Basel Committee’s main focus is on how the physical and transition risk drivers affect banks’ financial risks (credit, market, operational, liquidity risk, etc.) via micro- and macroeconomic transmission channels.

So far, the Basel Committee’s Standards and Guidelines have not covered the broader environment-related financial risks, nature-related financial risks or the ESG-related financial risks. The environment-related financial risks are broader than the climate-related financial risks and relate to the risks posed by exposure of banks to activities that may potentially cause or be affected by environmental degradation, i.e., air pollution, water pollution, scarcity of fresh water, land contamination, biodiversity loss and deforestation, and ocean acidification. Climate change itself could lead to environmental degradation and therefore, climate-related financial risks are a subset of the environment-related financial risks.

The nature-related financial risks, which are also broader than climate-related financial risks, refer to the negative impact on economies, banks and financial systems that result from: (i) the degradation of nature, including its biodiversity, and the loss of ecosystem services that flow from it (i.e., physical risks); or (ii) the misalignment of economic actors with actions aimed at protecting, restoring, and/or reducing negative impacts on nature (i.e., transition risks).

The ESG-related financial risks arise from the Environmental, Social and Governance factors, but there is no one universally accepted definition of these risks. The social factors could include labour and workforce considerations, human rights, inequality, discrimination, gender equality. The governance factors could include rights and responsibilities of directors, remuneration, bribery and corruption, etc.

Why has the Basel Committee restricted its work to climate-related financial risks? In the author’s opinion, this could possibly be because of the following: first, climate risk is more tractable and easier to quantify as climate change can be measured in terms of a single indicator, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, or their CO2 equivalents. Limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is a single goal agreed to by almost all countries. On the other hand, there is no single measure to quantify the environment-, nature-, or ESG-related impacts. Second, biodiversity (as a part of nature-related financial risks) is unique to a geographical location. The coral reefs and rainforests are important for different reasons in different areas of the world. If biodiversity is damaged in one location, it may not be possible to easily re-establish it in some other location. The concept of ‘offsetting’ impacts is more challenging for biodiversity than with GHG emissions. Third, while it is easier to incorporate nature- and ESG risks-related considerations in a bank’s strategy, governance structures, risk appetite and internal capital allocation process, it is much more difficult to prescribe a regulatory capital charge for these risks, because of the measurement issues mentioned above.

2. Addressing the climate-related financial risks within the existing Basel Framework

In December 2022, the BCBS published responses to frequently asked questions (FAQs) to clarify how climate-related financial risks may be captured in existing Pillar 1 standards of Basel III. The FAQ responses should not be interpreted as changes to the standards. The FAQ responses allow for flexibility while also encouraging banks to continuously develop their measurement and mitigation of climate-related financial risks. Some of the key changes brought about by FAQ responses are listed below.

The Standardised Approach for credit risk (after its update in December 2017, and now part of the Basel Framework) requires banks to perform ‘due diligence’ to ensure an appropriate assessment of the risk profile of their counterparties for risk management purposes and for assigning risk weights for regulatory capital purposes. Banks should assess climate-related financial risks as part of the counterparty due diligence. For determining the risk-weights, climate-related financial risks should be factored in either bank’s own credit risk assessment (under the Standardised Credit Risk Assessment Approach) or when performing due diligence on external ratings (under the External Credit Risk Assessment Approach).

Supervisors need to evaluate whether risk weights for real estate exposures are appropriate in their jurisdiction by considering, inter alia, climate-related financial risks (e.g., weather-related hazards, the implementation of climate-policy standards or changes in investment and consumption patterns derived from transition policies). Also, banks should determine whether the current market value of the financed property incorporates the potential changes in its value emerging from climate-related financial risks.

The ratings assigned to borrowers under the Internal Ratings Based Approach (IRB), should be based, inter alia, on a consideration of the climate-related financial risks (both physical and transition risks). A bank should add a margin of conservatism in its estimates of probabilities of default (PDs), loss given default (LGDs) and exposures at default (EADs), to account for the fact that historical data might be less satisfactory to capture climate-related financial risks and there may be data scarcity or poor quality of data relating to climate risk.

3. The 2023 Review of the Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision, which includes climate-related financial risks as an integral part of the banks’ risk management and supervisory practices

The Basel Core Principles are the de facto minimum standards for the sound prudential regulation and supervision of banks and banking systems. Although the Basel Core Principles are one of the 14 Standards that form a part of the Basel Framework, they are different from other Standards in that they are universally applicable to all banks in all jurisdictions (including the Basel Committee member jurisdictions). On the other hand, the Basel Committee expects that its members, at a minimum, fully implement the Basel Framework (i.e., all the 14 standards, including the Basel Core Principles).

The universal applicability of the Basel Core Principles allows them to be used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank as part of the Financial Sector Assessment Programme (FSAP) to evaluate the effectiveness of banking supervisory systems and practices in all countries, at all stages of economic and financial development. The universal applicability is ensured by adopting a proportionate approach, ‘both in terms of expectations of supervisors in the discharge of their own functions and in terms of the requirements that supervisors impose on banks. The concept of proportionality underpins the assessment and implementation of the Core Principles, even if it is not always directly referenced’.

The Basel Core Principles explicitly reference climate-related financial risks and mention that, ‘Amendments to CP8 (Core Principle 8) Supervisory approach and CP10 (Core Principle 10) Supervisory reporting would require supervisors to consider climate-related financial risks in their supervisory methodologies and processes and to have the power to require banks to submit information that allows for the assessment of the materiality of climate-related financial risks. Adjustments to CP15 (Core Principle 15) Risk management process would require banks to have comprehensive risk management policies and processes for all material risks, including climate-related financial risks, recognise that these risks could materialise over varying time horizons that go beyond their traditional capital planning horizon and implement appropriate measures to manage these risks where they are material. Adjustments to CP26 (Core Principle 26) Internal control and audit would require banks to consider climate-related financial risks as part of their internal control framework. Both bank and supervisory practices may consider climate-related financial risks in a flexible manner, given the degree of heterogeneity and evolving practices in this area’.

The inclusion of climate-related financial risks in the Basel Core Principles is a very important supervisory development. This will ensure that in all jurisdictions the supervisory agencies and banks implement climate-related policies, which will go a long way in addressing climate-related financial risks in the financial sector globally.

Amarendra is a Senior Financial Sector Specialist in the Financial Stability, Supervision and Payments pillar at the SEACEN Centre.