What is stress testing?

Banks fulfill an important function in the real economy by transforming redeemable deposits into long-term loans for investment to drive economic activity. Because a sound and resilient banking system is essential for all economic actors, central banks subject commercial banks to stringent capital and liquidity regulation and supervision. This is known as microprudential regulation and supervision, which sets minimum regulatory standards under normal financial market conditions and assesses compliance against these standards.

Bank balance sheets can be subject to periods of economic stress, such as during a deep recession. The underlying factors causing severe recessions can vary but are not the subject of discussion. What is important is that banks remain resilient during such periods and can continue to lend and support economic activities. Central banks assess the resilience of bank balance sheets by conducting annual stress tests. These exercises evaluate financial resilience by estimating bank losses, revenues, expenses, and resulting capital levels under hypothetical future adverse scenarios. These scenarios may extend to one year or cover multi-year periods. Since stress test results are conditional on the methodology, assumptions and scenario design, they are not intended to predict the outcome of a future severe recession or crisis.

Stress tests mainly focus on solvency because capital is core to a bank’s ability to absorb losses and continue lending. System-wide stress tests have become key tools for managing risks and guiding bank recapitalization. While solvency stress tests help assess and support banks’ capital planning, stress tests can also focus on liquidity. A liquidity stress test examines if a bank has sufficient cash inflows to withstand cash outflows in a stressed scenario. The failures of many US banks in 2023 demonstrate why liquidity stress tests can be equally important, given that solvency and liquidity risks are interlinked. However, compared to solvency stress tests, the methodology for conducting system-wide liquidity stress tests is less well-developed.

Since the global financial crisis, stress tests have become an important tool in supervisory dialogue with banks across many jurisdictions. One is the stress test conducted at the system-wide level, which is referred to as macroprudential stress tests. They have been developed to capture feedback loops, amplification mechanisms, and spillover effects across financial institutions and markets. Microprudential stress tests, on the other hand, assess the resilience of a single financial institution to adverse shocks. These tests are administered by microprudential supervisors and mostly conducted by banks themselves using their internal models, portfolio data and risk exposures. The results of these exercises will feed into Pillar 2 supervisory reviews and capital requirements. This blog focuses more narrowly on microprudential stress testing frameworks used by supervisory authorities.

Banks subject to stress testing: Range of practices

Stress testing is typically applied to systemically important banks – large institutions whose failure could pose significant risks to the broader financial system and the real economy. These banks are identified by regulatory authorities based on factors such as size, interconnectedness, and importance to financial system functioning. However, specific criteria and regulations regarding banks subject to stress testing vary by jurisdiction.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve Board conducts an annual microprudential stress test exercise under the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) to assess capital positions and planning practices of large firms. These stress tests apply to the largest and most complex institutions, including U.S. global systemically important banks, and those with US$250 billion or more in total assets, or with significant cross-jurisdictional activity, short-term wholesale funding, nonbank assets, or off-balance-sheet exposures. Banks with total assets between US$100 billion and US$250 billion that do not meet these higher risk thresholds are tested every two years. The Federal Reserve may also adjust the frequency of testing based on a bank’s financial condition, systemic importance, or exposure to risks affecting the U.S. economy.

The European Central Bank (ECB) conducts regular microprudential stress tests to assess the resilience of euro area banks to adverse financial and economic shocks under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). The ECB also runs other types of stress tests, including EU-wide tests coordinated by the European Banking Authority (EBA). Under EU law, ECB is required to conduct stress tests on supervised banks annually. Every two years, the EBA leads an EU-wide test in collaboration with the ECB, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), and national authorities, covering the largest banks and publishing both aggregate and bank-level results. In 2025, the ECB tested 51 major banks under the EBA exercise and 45 medium-sized banks under its own SSM stress test, complemented by a Counterparty Credit Risk (CCR) exploratory analysis.

The Deutsche Bundesbank conducts the Less Significant Institutions (LSI) stress test periodically, typically every two years. This microprudential stress test evaluates the earnings and resilience of small and mid-sized credit institutions in Germany. In the latest 2024 exercise, approximately 1,200 credit institutions directly supervised by the Bundesbank participated, covering 91% of credit institutions in Germany and accounting for 40% of total banking assets.

Within the SEACEN jurisdiction, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) requires all banks to conduct internal stress tests. Additionally, major banks, including domestic systemically important banks, must participate in industry-wide stress tests. Similarly, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) mandates that all banks participate in its annual macroprudential solvency test and supervisory microprudential stress testing. Moreover, banks are required to conduct their own internal stress tests for additional assurance. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) requires Indian banks to undertake both microprudential and macroprudential stress testing, focusing on credit, liquidity, and concentration risks over one- to three-year horizons. These are published in the semiannual Financial Stability Reports. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) employs supervisory stress tests using uniform shocks across credit, market, and liquidity risk parameters, with growing focus on climate-related financial risks due to the Philippines’ vulnerability to natural disasters.

Type and scenario design of microprudential stress tests

Central banks and regulatory authorities develop baseline and adverse scenarios, that reflect potential macroeconomic and financial market conditions. The adverse scenarios need to be sufficiently severe yet plausible to provide meaningful insights into bank resilience under stressed market conditions. The baseline scenario usually aligns with the central bank’s economic forecasts, while adverse scenarios explore various risk channels that could impact the banking system.

The design of adverse yet plausible macro-financial scenarios is an important part of the stress testing exercise. Stress scenarios simulate a severe, broad-based downturn affecting the real economy as well as financial markets and asset prices. Historical data can provide valuable input, but forward-looking elements and expert judgment must also be incorporated to account for new threats that affect asset values and macroeconomic outcomes. Climate change, cyber threats, and geopolitical tensions have emerged as significant factors that can have an adverse impact on the value of bank assets. The risk factors that are taken into consideration will determine the intensity of the shocks, the transmission channels and time horizon over which these factors affect the value of bank assets. Clearly, the design of the stress scenarios is a critical input into the exercise as they are the fundamental drivers of the quantitative results of the stress testing exercise.

The responsibility for the scenario design typically rests both with the supervisory authority and the central bank. The extent to which the exercises take a more micro- or a macroprudential approach influences which authority will take the lead. That said, most supervisory authorities – when they are independent from the central bank – do not have a formal process for coordinating supervisory stress testing frameworks with other domestic authorities. Consequently, it is often the central bank that coordinates the scenario design and stress testing exercise.

The type of stress testing exercise to be conducted can potentially influence the design of microprudential stress test scenarios. For example, stress tests can be conducted either from a bottom-up approach or a top-down approach. In the bottom-up approach, banks themselves calculate the impact to their balance sheet from the stressed scenarios while being subject to a prescriptive methodology and supervisory quality assurance. The bottom-up approach has the advantage of leveraging detailed internal bank-specific data, but they are resources intensive for banks and require extensive quality controls.

The bottom-up approach tends to be more suitable for a large number of smaller banks. For example, the Bundesbank conducts a comparative assessment of the resilience of less significant institutions (LSIs) in Germany involving around 1,200 banks by employing a bottom-up microprudential stress test. The baseline and adverse scenarios are those provided by ECB with the adverse scenarios being more specific for national LSIs. The adverse scenarios are usually specified in terms of macro-financial variables over the stress test horizon, which is typically 3 years. They include: cumulative fall in real GDP; cumulative inflation over the period; cumulative fall in residential and commercial real estate prices; and unemployment rate at the end of the forecast horizon.

In the top-down approach, the supervisors collect data from the banks and then use their own models and scenarios to assess the performance and balance sheet impact of the banks subject to stress testing. The top-down approach can also be used by authorities to challenge bank calculations by serving as a neutral benchmark and to initiate a dialogue with banks on their reporting of bottom-up stress tests. The Federal Reserve, for example, relies on a top-down approach for microprudential stress tests. Stress testing is done by using detailed portfolio data provided by banks but does not rely on models or estimates provided by banks emphasizing the independent nature of these exercises.

The governance structures for conducting stress tests are an important part of any supervisory framework. Governance includes the articulation of objectives and scope, and clarity on internal and external roles and responsibilities. Despite the importance of governance arrangements, a number of authorities do not have internal documentation that formally articulates roles and responsibilities for staff involved in supervisory stress tests. Moreover, there is also little theoretical guidance on exactly how one should design stress scenarios in several jurisdictions. In contrast to this, the US Federal Reserve publishes a set of documents for each stress test cycle that contain details about the scenarios and methodologies used in the supervisor-run stress tests. This includes both the baseline scenarios and adverse scenarios.

The baseline scenarios are based on the consensus projections from the Blue Chip Financial Forecasts and Blue Chip Economic Indicators that project US real activity, inflation and interest rates. The baseline scenarios for international variables also use the Blue Chip Economic Indicators as well as the forecasts in the IMF World Economic Outlook. The severely adverse scenario follows the Board’s policy statement on the Scenario Design Framework. The adverse scenarios are characterized by a severe global recession, including prolonged declines in both residential and commercial real estate prices that then spillover to the corporate sector affecting investment sentiment.

Having internal documentation that provides theoretical guidance on exactly how one should design stress scenarios including clearly established roles and responsibilities for staff involved in supervisory stress tests is an essential pre-requisite. The theoretical framework is necessary to ensure that the scenario design takes into account all material risks that affect the banking system and adequately capture macro-risks shared across banks. At the same time, adverse scenarios should be tailored to stress the key vulnerabilities and idiosyncratic risks in the asset mix of bank portfolios.

Linking stress test scenarios to bank balance sheet

The next step in the stress testing framework is to establish a clear link between macro-financial scenarios and the financial statements of banks. Scenarios by themselves are abstract constructs; their analytical value lies in translating them into measurable effects on income statements, balance sheets, and ultimately, capital ratios. This blog will illustrate how a bottom-up stress test can be conducted, showing how banks translate macroeconomic shocks into changes in credit risk, provisions, and capital adequacy to assess their resilience under adverse conditions.

The process begins by mapping macroeconomic stress scenarios, such as a sharp decline in GDP growth, rising unemployment, or higher inflation and interest rates, to bank-specific risk parameters. These variables capture the transmission of stress from the real economy to the banking sector. A decline in GDP growth reflects slower economic activity and reduced borrower capacity to service loans. Rising unemployment leads to household income stress and potential defaults, especially in retail and MSME loans. Higher inflation erodes real income and raises business costs, while higher interest rates increase debt servicing burdens and reduce asset valuations.

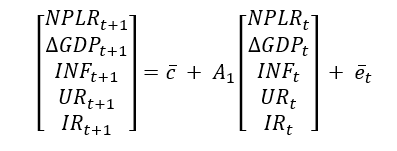

To quantify these linkages, banks often employ a Vector Autoregression (VAR) model to project the evolution of the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio under different macroeconomic conditions. The VAR framework captures how multiple time-series variables interact over time, allowing analysts to estimate how changes in the macro-financial environment affect banks’ asset quality.

For an n-dimensional vector of variables, a VAR model is typically written as:

y t = c + A1 y t−1 + A2 y t−2 + A3 y t−3 + e t

Here yt is a vector of endogenous variables, c is a constant vector, Aᵢ are coefficient matrices, and et is the error term. The parameters of the model are estimated from historical data using standard time-series techniques.

A simplified VAR model for projecting the NPL ratio (NPLR) may include five variables: NPLR, GDP growth (ΔGDP), inflation (INF), unemployment (UR), and interest rates (IR). Each variable depends on its own lagged values and those of the others, meaning macroeconomic shocks influence the NPL ratio both directly and indirectly through these interlinkages. If we restrict the number of lags in the VAR model to be one, we get the following simplified model:

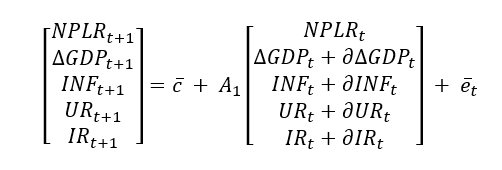

Once the baseline model is estimated, banks introduce stressed values for the macroeconomic variables to simulate adverse conditions. For example, a fall in GDP growth, a rise in inflation and unemployment, or higher interest rates represent the shocks at time t. These shocks are applied to the baseline values to generate new projections of the NPL ratio under stress:

Using quarterly data, stressed NPL ratios can be projected for an 8- to 12-quarter horizon. This allows supervisors to quantify how severe macroeconomic shocks such as a recession, high inflation, or sharp rate hikes translate into rising defaults across loan portfolios including retail mortgages, MSME, consumer, and corporate loans.

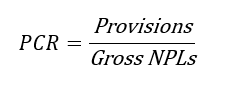

The projected gross NPL ratios, either by loan category or at aggregate level, must then be linked to loan loss provisions on the bank’s balance sheet. Banks typically rely on historical provisioning practices to estimate the additional provisions required under stress. However, supervisors may impose a minimum Provision Coverage Ratio (PCR) to ensure sufficient buffers:

A PCR set at 80 percent means banks must provision at least 80 percent of gross NPLs. Increases in provisions will directly reduce Tier 1 capital, as they are deducted from the bank’s capital to absorb potential losses.

Under the Basel III framework, capital is divided into Tier 1 (core capital) and Tier 2 (supplementary capital). Tier 1 capital comprises paid-up equity, retained earnings, and disclosed reserves, and is intended to absorb losses while the bank remains a going concern. Provisions for expected or incurred losses are deducted from Tier 1 capital because they are already allocated to cover known risks.

Tier 2 capital includes supplementary elements such as subordinated debt and general provisions. Under the standardized approach, Basel allows general provisions (not tied to specific loans) to be recognized in Tier 2, up to 1.25 percent of risk-weighted assets (RWA). However, specific provisions linked to identified NPLs do not qualify as capital. Provisions arising from stress tests must therefore be deducted from Tier 1 capital.

If the bank has no Additional Tier 1 (AT1) instruments, the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio depends solely on available Tier 1 capital. The additional provisions required under stress reduce CET1 directly, lowering the numerator of the ratio. Under the standardized approach, RWA for credit risk in the denominator typically remains unchanged. While market risk RWA may rise in periods of high volatility, this effect is considered separately. Ignoring potential changes in net income, the stressed CET1 ratio can be expressed as:

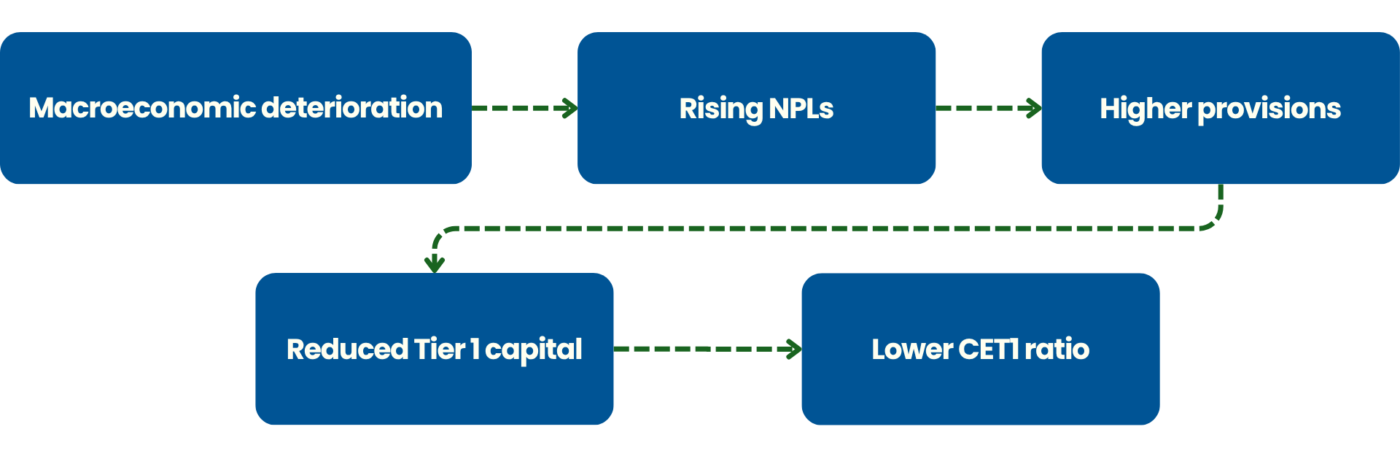

This formulation shows how macroeconomic deterioration leads to rising NPLs, higher provisions, lower Tier 1 capital, and a lower capital adequacy ratio. It provides supervisors with a consistent framework to quantify solvency pressures and assess whether banks maintain sufficient buffers to withstand severe but plausible macro-financial shocks.

Action plan to address capital shortfall

Once stress tests identify potential losses and capital depletion, the focus shifts to how banks can restore resilience. This stage transforms the exercise from a diagnostic tool into a capital planning process. If stress test projections indicate that a bank’s capital ratio would fall below regulatory thresholds under the adverse scenario, management and supervisors must consider remedial measures.

Capital shortfalls can be addressed in several ways. Banks may raise fresh equity from markets or parent institutions, retain a larger share of earnings by limiting dividend payouts, or adjust their balance sheet composition by reducing riskier exposures. In some cases, deleveraging may be necessary, though this can restrict credit supply to the economy and amplify downturn effects. Supervisors therefore balance the need for capital strength with the need to sustain lending to the real economy.

The severity of the shortfall guides the response. Minor shortfalls may be met through dividend restrictions or capital conservation buffers, while more significant gaps may require targeted recapitalization or restructuring. Importantly, stress test results often serve as inputs to supervisory discussions on recovery and resolution planning, ensuring that banks maintain credible strategies to withstand future shocks.

Communicating results of stress tests

The credibility of stress tests depends not only on robust methodologies but also on effective communication. How results are presented to banks, markets, and the public directly influences confidence in the financial system. Clear communication signals that supervisors are vigilant, that risks are being monitored, and that corrective actions will be taken when necessary.

Authorities often adopt a tiered communication strategy. To banks themselves, detailed feedback is provided to guide capital planning, internal risk management, and governance improvements. At the system-wide level, aggregate results are typically published, showing how the banking sector as a whole would perform under adverse conditions. Some jurisdictions, such as the United States and the European Union, also disclose detailed bank-level outcomes. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve announces stress test release dates in advance and publishes comprehensive, bank-specific results under the CCAR and the Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test (DFAST) frameworks, framing them in a forward-looking narrative of capital resilience. Similarly, the ECB and EBA publish aggregate and bank-level results, but with detailed context on supervisory follow-up, so that market participants understand not just the weaknesses but also the remedial steps being taken. By contrast, authorities such as BNM and MAS emphasize system-wide resilience in their public reports, while keeping institution-specific results confidential. This approach reflects differences in market structures and the need to safeguard stability in smaller or more concentrated financial systems.

At the same time, communication requires careful balance. Overly optimistic messages risk undermining credibility, while overly pessimistic ones may trigger adverse market reactions. Supervisors therefore focus on transparency in assumptions, scenario design, and interpretation of results, while emphasizing that stress tests are conditional “what if” exercises rather than forecasts. Some central banks, such as the Bank of England, also make results more accessible by supplementing technical reports with visual summaries and interactive tools, while RBI integrates stress test disclosures into its Financial Stability Reports with educational material to improve financial literacy. These diverse practices show that communication strategies can be adapted to local contexts, but the underlying principle remains the same: effective communication builds trust and ensures that banks, markets, and the public understand both the purpose and limitations of stress tests.

Conclusion

Stress testing has become one of the most important supervisory tools in safeguarding financial stability. In this blog, the focus has been on microprudential stress tests because they provide the clearest view of how shocks affect individual banks’ balance sheets and capital positions. These exercises are practical and widely used, helping supervisors and banks plan ahead, address capital shortfalls, and make sure institutions remain resilient under stress.

Macroprudential stress tests can capture broader feedback loops and systemic risks, but microprudential stress tests remain the foundation of supervisory practice. As emerging risks such as climate change, cyber threats, and geopolitical shocks reshape the financial landscape, stress testing will need to evolve. Still, its core purpose stays the same: to build confidence that banks can absorb losses and continue supporting the real economy, even when conditions are difficult.

Masyitah Rosmin is a Research Associate at the SEACEN Centre.