“To reach net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, entities operating in most sectors must undergo a major transformation. The key tool that will enable this transformation is the development of a transition plan that is science based, coherent, comprehensive, transparent and covers all material scopes of emissions and business activities.” CBI Report on Scaling Credible Transition Finance – ASEAN

- Transition finance straddles along the spectrum of sustainable finance. The core concept entails a credible strategy of reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, particularly in sectors that are considered high emitting ones. This involves a pathway to achieving net zero within a timeframe consistent with the Paris Agreement and Sovereign Climate Strategies;

- The low-carbon transition pathway will be unique for each economy, given their socio-economic context but a common definition of the transition path will provide benchmarking for progress and financing thereof;

- Transition financing is key to achieving the net zero target in Emerging Markets and Frontier Markets;

- Private capital mobilisation through cross-border capital flows to fill the transition finance gap will be critical but the role of public sector in underwriting and sharing some of the risk through instruments, such as partial guarantees, will be equally important;

- Regulators in Emerging Markets and Frontier Markets in Asia have increasingly been focusing on the pulse of sustainable finance but the nature of it is more complex given the importance of transition finance;

- Regulators are now coordinating more closely in the three areas of climate-related disclosures and data, the inter-operability of classifications and regulations, and common definitions of credible sectoral transition paths;

- Convergence on these aspects of the framework will foster cross-border transition finance related capital flows from global climate investors in debt and equity capital markets, banking and other forms of financing.

Emerging and Frontier Markets in Asia can achieve Net Zero through Transition Finance

Transition financing is key to achieving the net zero target in Emerging Markets and Frontier Markets (EMs & FMs). But private sector climate finance, including finance mobilised by institutional investors in public markets and private markets, will be crucial in funding the immense investment needs related to climate mitigation and adaptation in EMs & FMs in Asia. All key policy initiatives point to the need to leverage global capital flows, notably capital markets, in support of the climate transition in emerging markets, with the bulk of financing needs arising in Asia. In addition, the role of the public sector to provide incentives, including some underwriting and sharing of risk will be crucial in broadening and deepening climate finance.

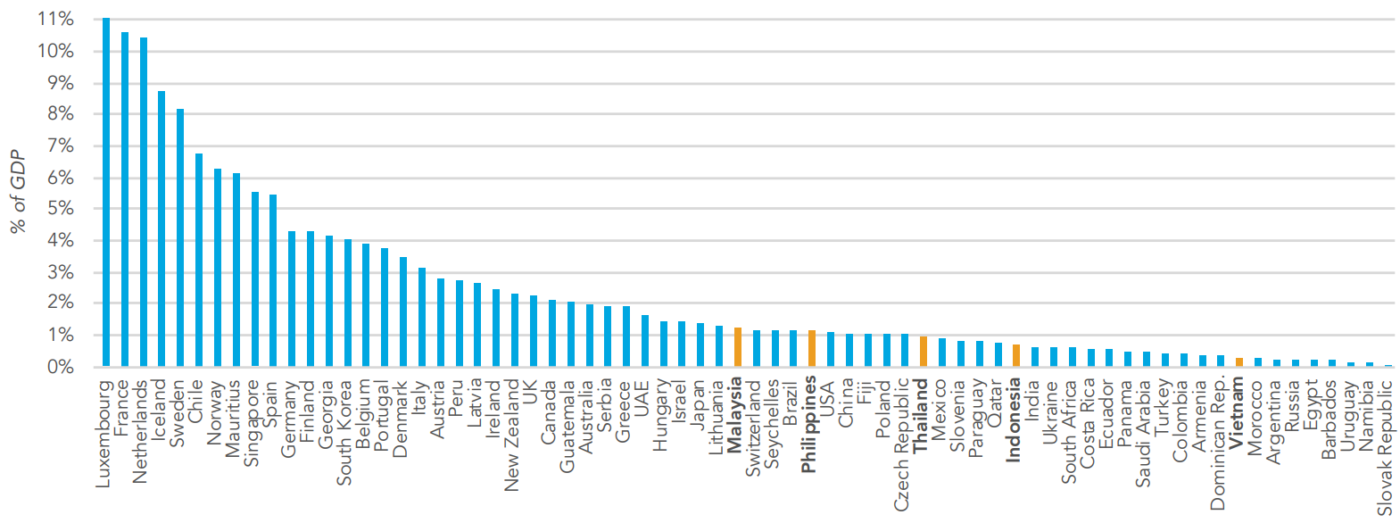

Asia could clinch this opportunity to deepen its own markets for sustainable debt markets. Despite significant progress in developing bond markets across the ASEAN and broader Asia, the sustainable debt markets are not very deep and liquid as underlined by the figure below. The need to close the transition financing gap can be energised by broadening the investor base, both from this region and other advanced markets such as in Europe, where sustainable investments feature more prominently on the radar of the investors. Such greening of the debt capital markets will have to go hand-in-hand with a regulatory framework that strikes the right balance between rules and measured incentives.

Source: World Bank.

The Role of Cross-Border Capital Flows in Enabling Transition Finance

Global institutional investors are increasingly mandated to limit risks related to excessive exposure to fossil-fuel technologies and to invest in companies that are progressing towards a low-carbon profile. A benchmark could be more advanced sustainable investment frameworks like in the EU, where there has already been a shift in the interpretation of investor ‘fiduciary duty’ in the main capital markets law (MiFID II). Some investors go even further and actively seek allocations in projects that have a high impact in reducing GHG emissions. This would call for much larger allocations in emerging markets, where the marginal costs of carbon emissions reductions are much lower than in most advanced countries.

There is a strong rationale for capital flows to meet the transition finance gap in EMs & FMs. Institutional investors, including in the EU, where the green finance sector is rapidly developing, would likely be looking for diversification and comparable risk-adjusted returns in the sustainable finance sector which will undoubtedly include transition finance. Total assets of institutional investors from the advance economies are far more significant than their share in global activity or capital markets especially because of the long-standing capitalisation of pension funds many of these economies and a relatively mature insurance industry. Including the UK, European institutional investor assets are estimated at roughly USD25.7 trillion. The EU’s external asset position in portfolio debt and equity amounted to just under EUR11 trillion according at end-2022.

An Opportunity for Global Climate Investors to Reduce ‘Home Bias‘

Home bias in asset allocation has been predominant among advanced economy institutional investors. For example, the conundrum for EU policy makers has been that these assets predominantly remain in low-risk financial instruments such as state bonds within the EU. For pension funds the allocation within the EU is 63 per cent and for insurance companies 81 per cent. By contrast, allocations of funds to lower and middle-income economies excluding China are extremely limited at only 4 per cent and 1.3 per cent respectively. This proclivity to allocate portfolios in assets in the asset manager’s home base is explained by a mix of macroeconomic and regulatory factors and by incentives within fund management firms. These obstacles of course apply in equal measure to climate-related financial instruments.

So far, sustainable capital market finance has fallen well short of policy ambitions not just in terms of scale but also in being largely limited to investors’ own home markets. Private sector climate finance seems highly fragmented between markets, as the observed cross-border mobility has been quite limited. For instance, figures for global spending on climate related projects indicated that 84 per cent of finance was raised and spent domestically. As a measure of north-south flows, only about 7 per cent of climate finance was directed from OECD to non-OECD countries. A more detailed study on portfolio allocations by global asset managers of bond and equity portfolios showed similarly limited allocations in emerging markets.

The Case for EMs & FMs for Attracting Cross-Border Capital Flows for Transition Finance

- There needs to be a common understanding of the term ‘transition finance’. A simple definition of transition finance can be helpful – financing that entails the reduction of GHG emissions mainly in sectors that are considered high emitting sectors and yet can find a reasonable pathway to achieving net zero within a timeframe consistent with the Paris Agreement and Sovereign Climate Strategies.

- Regulatory fragmentation with regards to green/transition taxonomies and disclosure rules or standards across institutions and jurisdictions remain an important area of concern. The rulemaking has mainly evolved with limited coordination between jurisdictions while regulatory barriers continue to pose impediments for investor to consider financial instruments across markets, limiting cross-border capital flow mobilisation for climate finance towards Emerging and Frontier Markets.

Taking a deeper dive on the pre-existing impediments to sustainable finance, here are some of the challenges:

- A first and fundamental barrier to sustainable finance investment in emerging markets is due to gaps in climate-related information. Sustainable finance instruments rely to a much greater degree on transparency and disclosure by the borrower or issuer than is the case for regular financial instruments. Only on the back of good data and disclosures from individual asset level exposures can lenders or investors account for climate risks and opportunities in their portfolios. A World Bank survey of financial institutions active in the Asia region found that about 88 per cent of respondents saw information as a key constraint. Demanding regulatory standards in advanced countries, such as the EU or the UK are reinforcing this barrier. Under the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) which has been in effect since 2021 financial firms and asset managers, including pension funds and insurance companies, need to disclose how sustainability factors and risks are integrated into investment processes. A recent report by an expert group appointed by the EU also described this regulation as a barrier for exposures in emerging markets. In the absence of good corporate ESG data, investors often turn to country-level ESG ratings, even though these turn out to be highly correlated with income levels and may be a poor reflection on the sustainability characteristics of an individual investment. International initiatives, such the new International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) now provide a global baseline for good disclosure which is gradually being introduced in a number of Asian markets. Regulators are preparing their corporate and financial sectors for such standards and have begun to build a supporting ecosystem in the accounting and auditing professions. This may need to be matched with coordination with advanced markets so that better disclosure can meet investors’ standards in a wide range of jurisdictions.

- A further barrier is the lack of a common terminology for sustainability, which is often interpreted differently across key regions and markets. By now about 47 national taxonomies of sustainable activities and investments exist. Only what is defined as ‘green’ can be included in sustainable finance instruments such as green bonds under each standard. Naturally, there is agreement about some key technologies that are clearly consistent with the low-carbon future, say in the case of renewable energy or electric vehicles. Yet, some regulators have included intermediate technologies, such as gas-fired power and infrastructure, which may be needed in the transition though which may ultimately not be consistent with an acceptable climate outcome. Local sustainability goals, such as biodiversity, and social or governance safeguards further complicate the picture for cross border investors. Exposures need to be tested against technical screening criteria, such as emissions intensity. Some regulators are now trying to strengthen the ‘inter-operability’ of their respective taxonomies. Common frameworks, such as the ASEAN Taxonomy, may help in that effort. In the absence of a global agreement there will need to be many bilateral interactions between regulators to ensure mutual recognition (in the case of foreign direct investment governments have adopted over 2,500 bilateral investment treaties). Ultimately, there should be little to prevent global investors with a climate mandate from including in their portfolio a green bond fund or a transition bond fund structured in one of Asia’s financial centers.

- Finally, regulators in emerging markets and advanced countries may have a more fundamental difference on the nature of transition finance. This type of investment is not directed into specific green assets or activities but rather funds enterprises with a credible strategy in the low-carbon transition. At the core of such a strategy is a transition plan that sets out a path towards net zero. While there has been much progress in fleshing out the key elements of such a plan, there is little international agreement on its defining feature: how steep the decarbonisation path is and the timing of a net zero target (a recent NGFS report did not prescribe such guidance). This may prevent investors with ambitious national transition paths from holding assets in emerging markets where targets may be more distant, or near-term decarbonisation less ambitious. For instance, under recent EU legislation on corporate disclosures, a company that claims to have a transition plan needs to set out capital expenditures and internal incentives that prepare for global warming of no more than 1.5 degrees. Private standard setters and a number of investor alliances also adopt such targets. Asian regulators can engage in a number of initiatives to coordinate the nature and ambition of sectoral transition plans. Companies that adopt credible plans then stand to benefit from a growing investor appetite for such transition plans.

Asian market regulators who seek to keep markets open and utilise public and private markets for funding transitioning to green investments can address these obstacles through a mix of domestic market reform and engagement in international initiatives. Regulators are now coordinating more closely in these three areas of climate-related disclosures and data, the inter-operability of classifications and regulations, and common definitions of credible sectoral transition paths.

Indeed, the opportunities presented by transition finance can be a ‘call for action’ to all stakeholders, including regulators, market participants, and the public sector, to collaborate in addressing these challenges. While the close regulatory harmonisation within the EU is no doubt unique, it seems to have supported the emergence of a liquid green bond and bank lending market for which cross-border integration is in fact stronger than is the case for the financial market as a whole. An ECB study showed that strong investor demand in the sustainable finance asset class translated into cross-border exposures with economies in which green assets emerged (even though this outward orientation then diminishes). This experience may well be instructive for financial integration through sustainable finance within the ASEAN and wider Asia region, and perhaps for openness for global green and transition finance mobility more broadly.

Mangal Goswami

Mangal Goswami is the former Executive Director of The SEACEN Centre. He served from 2019 - June 2024.