Author’s note: This blog is based on a published article: CHADWICK, M., CHERRY, R. and GALIMBERTI, J.K. (2025), Nonresponse Bias in Household Inflation Expectations Surveys. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.70002

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their corresponding institutional affiliations.

Measures of household inflation expectations are fundamental inputs for modern central banks, serving as key determinants of prices and uncovering whether beliefs are anchored to the inflation target. However, our recent research using microdata from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s (RBNZ) Household Inflation Expectations survey reveals a widespread measurement issue: item nonresponse bias (See Chadwick, Cherry and Galimberti, 2025).

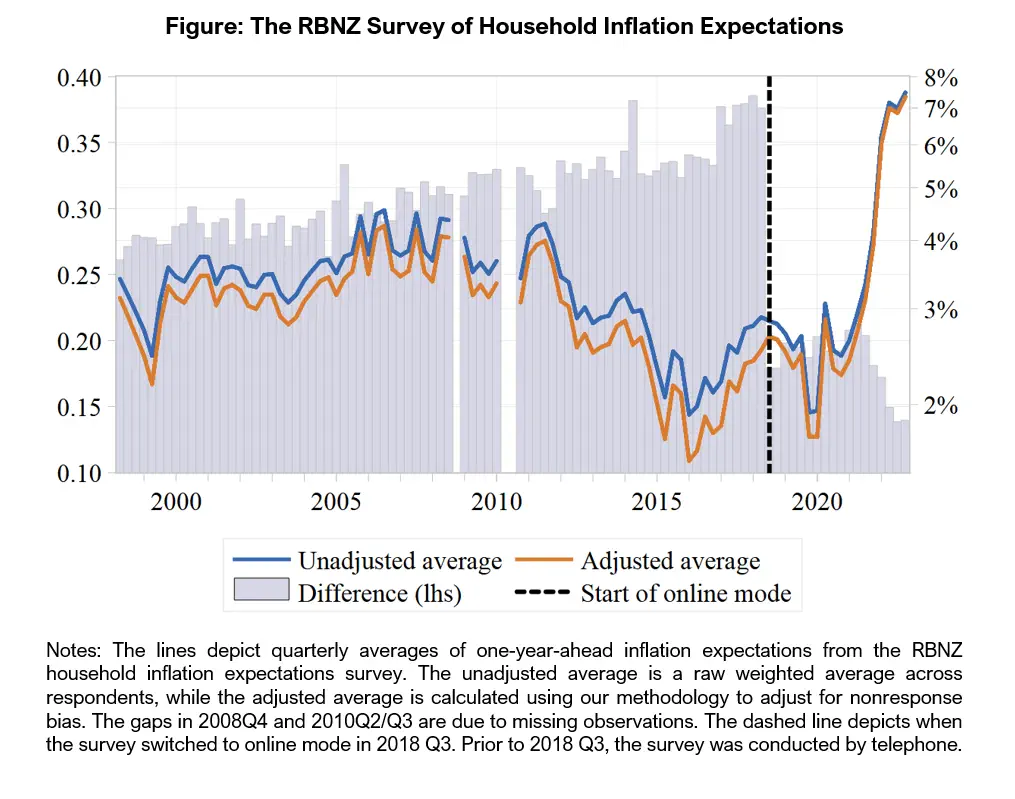

This bias happens when survey participants opt not to answer the question on expected inflation, and these nonresponses are not random. We find that typical survey summaries substantially misrepresent the population’s beliefs, artificially elevating overall expectations and skewing perceptions of demographic differences (See the Figure below).

The Silent Skew in Survey Data

Analysis of the RBNZ microdata (1998 Q2 to 2022 Q4) reveals a significant challenge: on average, roughly 44% of respondents did not provide an inflation expectation. Crucially, the missing voices belong systematically to specific demographic groups:

- Young individuals (under 25),

- Female respondents (who were about 20% less likely to respond than men),

- Low-income households,

- Individuals from minority ethnic groups (specifically Māori, Pacific Islanders, and Asian).

This non-random selection process indicates that relying only on responses from the interested minority can undermine the accuracy of survey data in reflecting the population’s true beliefs.

Quantifying and Correcting the Error

We use a sample selection model, specifically, the Heckman selection model, to quantify and adjust for the item nonresponse bias. This methodology is essential because typical adjustments, such as random imputation, fail to account for the systematic sociodemographic factors driving nonresponses, thus yielding a similarly distorted picture.

The adjustment reveals two critical findings:

- Aggregate Expectations are Lower: The unadjusted aggregate inflation expectation series is positively biased. After correction, the adjusted series shifts down by about 0.3 percentage points on average over the full sample period (annual inflation between 1998 and 2022 was 2.26% on average). This adjustment reduces measurement errors, thereby improving the reliability of these estimates as critical inputs to monetary policy decision-making, potentially leading to better policy responses.

- Heterogeneity is Redefined: Correcting for selection bias fundamentally alters the understanding of differences across groups. Factors such as gender, ethnicity, and income, which previously showed systematic differences in observed expectations, become statistically insignificant after correction. This suggests that being female, having low income, or being a minority member determined participation in the survey, rather than defining the group’s average expectation. The one exception is age: the difference in expectations between older and younger individuals increases in magnitude after correction, with older individuals overpredicting inflation more strongly.

Furthermore, item nonresponse bias impacts perceptions of disagreement. Correcting the data generally reduces disagreement in measured inflation expectations, both across and within subgroups.

The Power of Design and Economic State

The research also offers crucial insights into how central banks can mitigate this bias ex-ante through survey design.

A significant finding concerns the RBNZ’s shift from telephone to online survey mode, starting in 2018 Q3. This change led to a dramatic drop in the nonresponse rate (to about 24% since the shift). Critically, the online mode made the survey more inclusive, substantially reducing nonresponse gaps across demographic groups such as gender and ethnicity.

Moreover, the willingness to respond is state-dependent. Response rates tend to increase nonlinearly when the previous quarter’s inflation rate moves significantly away from the central bank’s target range. This may imply that when inflation moves out of the “rational inattention” zone, price changes come into sharp focus, increasing survey participants’ ability or willingness to respond to the survey.

Policy Recommendations for Asia-Pacific Central Banks

Given that the importance of item nonresponse is likely to be even greater in less developed areas across the Asia-Pacific, tackling this methodological issue is crucial for regional central banks (CBs) to ensure their household survey data accurately informs monetary policy decisions.

- Prioritise survey modernisation and inclusion: As our research illustrates, strategic transition of inflation expectations surveys to online modes can help CBs. This dramatically improves response rates and reduces demographic nonresponse gaps. However, policy must ensure digital accessibility to prevent introducing new selection bias against populations with limited internet access or technological proficiency.

- Mandate advanced methodological correction: Policymakers must move beyond simple weighting schemes designed for unit nonresponse. CBs can adopt different sample selection models to adjust measures of aggregate and subgroup inflation expectations. This adjustment can provide a more accurate, downward-shifted aggregate estimate and correctly show that much of the observed heterogeneity by gender, income, and ethnicity is an artefact of selection bias rather than an actual difference in expectations.

- Implement layered and targeted communication: Recognising that high nonresponse rates correlate with specific socioeconomic factors (young, female, low-income, minority), CBs can employ inclusive communication strategies. This requires developing layered messaging that tailors the complexity of policy content to diverse audiences, especially those with lower economic literacy, to enhance public understanding and trust.

- Leverage macroeconomic moments: CBs should strategically use periods of heightened inflation dynamics (when response rates are naturally higher due to increased attention) to amplify monetary policy communication and enhance public engagement, shifting focus from financial markets to the general public.