INTRODUCTION

India embarked on a journey during the last decade to build digital public infrastructure to provide access to finance to a very diverse population. Building the digital public infrastructure began with the Aadhaar unique biometric identity issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI). By empowering the citizens of India with a digital identity, the access to banking services was opened to a large population of unbanked people in India.

Empowering people with digital identity is only a start as access to banking services must be supported by the necessary digital infrastructure to facilitate payments. Towards this goal, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) launched the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in 2016, which is operated by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), a non-profit entity. The payments made through UPI fall under the category of retail credit transfers. As of first half of 2024, the UPI transactions contributed to less than 9 percent by value of digital transfers, but over 80 percent of the volume of the digital payments in India.

Gaining access to a bank account and having enabling services to make payments is a fundamental building block for financial inclusion. But financial inclusion is much broader in scope in the sense that it also requires the provision of suitable, affordable and quality financial services – meaning the access to affordable credit. Getting access to affordable credit is the most difficult nut to crack in the financial inclusion agenda. That is because the extension of credit is a private contract between the lender and the borrower. Information asymmetries, collateral constraints, and difficulty in enforcing legal contracts in a timely manner are all major frictions in access to credit, particularly for those who are not well served by the existing financial service providers. This last mile in the financial inclusion journey is therefore a significant challenge for every country.

The main focus of this blog is to present the novel approach taken by India to complete the last mile of the financial inclusion journey. The main tool being used to achieve this objective has been to leverage the IT infrastructure and the skill sets in this area to build a data repository that aggregates information across different digital platforms. They include the digital identity using Aadhaar, available credit history information across multiple lenders, and information from land registers. The data repository’s primary objective is to address the information asymmetry problem in credit allocation decisions, which is an important source of friction.

AADHAAR: THE FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL PUBLIC GOODS

India’s digital public infrastructure serves as the backbone of inclusive finance, e-governance and innovation. All this began with the simple idea of providing a digital identity to the citizens of India under the Aadhaar project. This project, launched by UIDAI, was the turning point in India’s digital public infrastructure which provided over 1.3 billion Indians with a unique, verifiable identity linked to their biometrics and minimal demographic data. It soon became evident that Aadhaar was not just a biometric ID for the people – its scope was much broader. The Aadhaar identity suddenly transformed the lives of many Indians by enabling them the access to services ranging from banking and subsidies to insurance and mobile connectivity.

Aadhaar made online transactions possible at scale with over 125 billion e-authentications taking place since it started. Moreover, by enabling Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT) of over $450 billion, it has helped eliminate leakage, ghost beneficiaries and middlemen in welfare schemes resulting in estimated savings of $42 billion. It soon became clear that India’s innovation was not just technological, it was also architectural. Instead of building vertical siloed platforms for health, finance or welfare, India built a horizontal, open, interoperable digital payment infrastructure (DPI) layer that could plug into any sector. Aadhaar was the first pillar of the digital revolution, the next one being UPI that used this infrastructure to embark on the payment journey.

AADHAAR TO UPI: THE PAYMENT JOURNEY

By 2015, the Aadhaar-enabled ecosystem had ensured that nearly every Indian could be identified and authenticated digitally. But the financial system remained fragmented, slow and exclusionary. As of 2008, less than 20 percent of Indians had access to a bank account. Moreover, even as of 2018 more than 80 percent of transactions were cash based according to the 2019-20 RBI annual report. Use of Point of Sale (PoS) terminals was also very limited and accepting small-value digital payments were unattractive for merchants so that they were not offering these services.

It is in this context that the UPI was launched in 2016 by the NPCI with the intent to resolve inefficiencies in small value digital payments. The Aadhaar to UPI journey marked the next significant leap in India’s digital payment landscape. The journey reflects India’s commitment to a digitally inclusive economy, where Aadhaar ensures identity verification and UPI enables instant, accessible banking. Together, they redefined how India transacts in the digital age. The UPI, which appeared at the outset to be a payment App, was in fact a protocol layer that allowed any bank, fintech or payment service provider to offer real-time, low-cost, interoperable payments using just a mobile number or biometric ID.

The success factor of the UPI was that it abstracted away complexity requiring no Indian Financial System Code (IFSC), no branch name of bank or password to be entered. All that was needed to make peer-to-peer transfers was a biometric ID making transfers as easy as sending a text message. In a nutshell, UPI merged multiple banking features into a single platform to enable seamless money transfers using simple identifiers such as a Virtual Payment Address (VPA), mobile number, QR code, or Aadhaar number. As a public digital rail with open Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and zero MDR (merchant discount rate), it unleashed innovation and price competition.

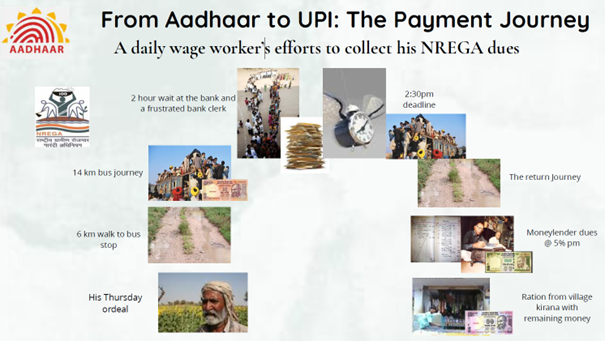

By January 2025, UPI has been processing 17 billion transactions a month worth $6.42 trillion annually. That is more than the GDP of 150+ countries. Around 600 banks and fintechs are live on UPI helping to connect to almost every Indian household. But statistics do not reveal a more profound transformation taking place in the daily lives of people in rural India. A compelling example is the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), which is a demand-driven wage employment programme offering job security to rural households in India. Eligible beneficiaries are issued a NREGA Job Card as an identity proof. Using this card, NREGA beneficiaries can seek employment.

Before the launch of UPI, collecting the eligible wages under the NREGA scheme involved often a day’s commute to the cash distribution centre involving transport cost and lost wages for the day. Typically, this amounted to almost 20 percent of the monthly wage received under the scheme. But after Aadhar and UPI were launched, these wages are now being directly credited to the workers’ bank account. The credit in the workers bank account can then be used to pay for purchases at the local grocery store in the village or withdrawn as cash from a micro-ATM using just a fingerprint identification and no transaction charges.

The UPI scheme has also dramatically reduced cross-border remittance fees for migrant workers. For example, a migrant worker in Singapore used to pay 5 to 10 percent of his income as remittance fees and waited several days for the finality of settlement. But now with the UPI’s cross-border expansion, the migrant worker can send money home to the bank account of his family almost instantly at near-zero cost.

Building on the digital identity provided by Aadhaar, the UPI has enabled cheap and efficient peer-to-peer and merchant payments using the digital public infrastructure for the most populous country in the world. But there remained one unresolved frontier which is access to credit. Indeed, having access to a bank account and to be able to make small value digital payments at zero cost is an important leg of the financial inclusion journey. But completing this journey requires that those who have been financially excluded in the past, such as small farmers and family-owned businesses, also have access to credit. India has started the last mile of the financial inclusion journey by building the Unified Lending Interface (ULI), which is discussed next.

ULI: THE LENDING REVOLUTION

Despite UPI’s resounding success in enabling low cost and efficient payments, access to formal credit has remained dismally low for a significant share of India’s population. Even for India’s 63 million micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), the access to formal institutional credit remains a challenge. Current estimates indicate that only about 14 to 15 percent of MSMEs have access to institutional credit with the credit gap being around $530 billion.

There are multiple reasons why access to formal credit remains a challenge, which are highlighted below.

- Fragmented data systems: Existing practices still rely on paper documents, scattered databases, and manual verification of borrower creditworthiness.

- Lack of financial visibility: Small businesses and informal workers often do not leave a digital footprint, making their cash flows and creditworthiness difficult to assess for banks.

- Bureaucratic hurdles: Lengthy collateral verification process, repeated KYC document submission, and offline paperwork make small loans costly to acquire and slow to process.

- No collateral: Many small businesses have to raise unsecured loans, and when there are no verified financial statements to support the loan application, formal lenders either reject the applications or charge high interest rates that make such loans unattractive.

As India’s success story on transforming the payments landscape gathered pace, the gap between making payments and granting loans widened. In addition to the identified challenges mentioned above, much of the credit documentation for small loans granted in the past remained in paper form or were in unconsolidated and scattered databases. Even when diverse sources of financial and non-financial data required by lenders for digital credit delivery exist, they often lie in silos across different entities. Lenders, as part of their credit underwriting, need to individually connect with all these data sources, making it highly cumbersome and costly.

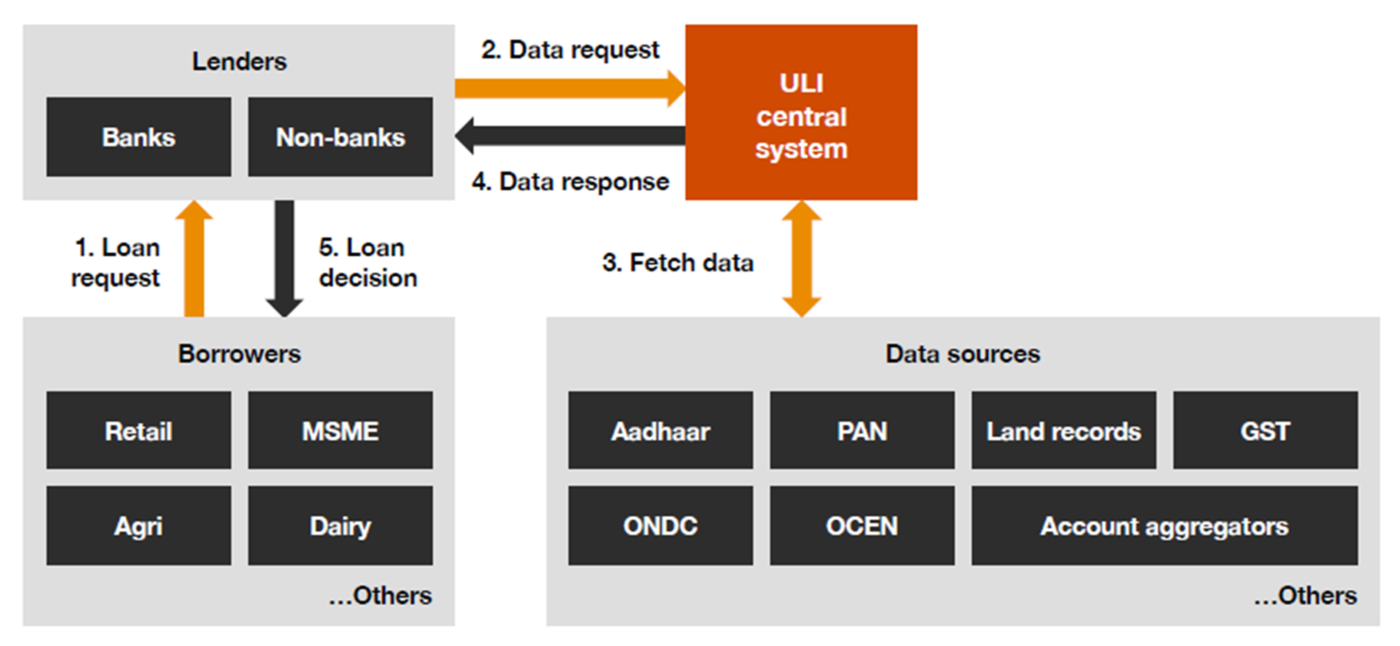

What India needed was to build on the success story of UPI to create a technology platform to facilitate the efficient delivery of frictionless credit. Tasked with this deliverable, the Reserve Bank Innovation Hub (RBIH) developed the ULI platform which is a backend protocol stack that connects lenders to real-time, verified, multi-source data through consent-based APIs. The platform helps to unlock critical financial, non-financial and alternate data for lenders including digitised state land records, milk pouring data from milk federations, satellite data and property search services through a single interface (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Functional Architecture of ULI

ULI’s architecture is grounded in the following essential design principles that together support its mission to deliver inclusive, scalable and efficient credit access.

- At its core, ULI enables data consistency through standardised protocols, allowing different financial entities to speak the same digital language.

- It brings legacy systems into the modern era through seamless API integration, while also converting manual and paper-based processes into fully digitised ones.

- The platform is built with privacy as its heart with every transaction being governed through consent-by-design frameworks that ensure data is accessed securely and only with user approval.

- ULI is designed to be both scalable and vendor-neutral, ensuring it can serve institutions of all sizes without locking them into proprietary technologies.

- The infrastructure remains open to all regulated lenders, encouraging healthy competition and collaboration across the financial ecosystem.

In the realm of personal credit, ULI supports individuals who may be dealing with time-sensitive needs such as medical emergencies or bridge financing. By digitally aggregating identity, health and asset data from multiple verified sources, ULI empowers lenders to offer timely, data-driven decisions while reducing operational overhead. These scenarios reflect a broader shift toward frictionless credit delivery, where ULI plays a pivotal role in enhancing transparency, speed and trust across the financial ecosystem. As adoption scales, ULI is expected to become a cornerstone of India’s digital credit architecture like UPI has done for payments.

In conclusion, UPI was India’s digital payment revolution. ULI is India’s digital credit revolution. Together they form the two engines of inclusive finance. The story of India’s FinTech journey from Aadhaar to UPI to ULI is an example to see what is possible when technology, regulation and infrastructure converge around public interest. With DPI as the foundation, India is no longer just consuming financial innovation, but it is exporting it. ULI’s rollout may well define the next decade of equitable credit access, just as UPI defined the last decade of digital payments.