1. Introduction

The digitalization, the rise of crypto-assets and the advancement of technologies, such as distributed ledger technologies, have fuelled an unprecedented wave of innovations in payments and spurred many Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) projects over the past decade[1]. Central banks worldwide have been actively exploring solutions to preserve financial stability and safeguard monetary sovereignty in an increasingly digital economy. Meanwhile, private actors – both established institutions and new entrants – have quickly perceived the potential benefits of issuing their own means of payment. One of the prominent initial efforts to issue a stablecoin dates back to 2019, when Meta (Facebook at the time) sought to launch its own currency backed by a basket of major currencies. This effort triggered a series of policy responses, including the G20 roadmap on cross-border payments[2]. Yet, for several years, stablecoins remained largely confined to the decentralized finance ecosystem.

However, in early 2025, the U.S. decision to ban a domestic CBDC and rather support USD-backed stablecoins issuance under the GENIUS Act[3] signalled a turning point. This move accelerated stablecoin development and raised two critical concerns. First, the risk of a “privatization of money,” where the international monetary and financial system (IMFS) could revolve around one or several privately issued stablecoins—undermining central banks’ role as anchors of financial stability and introducing challenges around liquidity, interoperability, and systemic risk. Second, the prospect of “digital dollarization,” where dollar-backed stablecoins dominate payment systems in multiple jurisdictions, potentially threatening the monetary sovereignty of other countries.

Against this backdrop, CBDCs and stablecoins could be increasingly perceived as rivals in the long run, not only in the retail space where both can be used as payment instruments, but also in the wholesale domain where they would compete in areas such as settlement, cross-border transfers, and liquidity management. Yet, they may also complement each other, with public infrastructures providing a foundation for private innovation. This blog article will thus examine whether CBDCs and stablecoins can be viewed as complements in both the retail and the wholesale payments sphere, before discussing policy implications and giving concluding thoughts.

| Box No.1 : CBDCs and Stablecoins: Two Distinct Instruments Serving Different Function in Payment Landscape Central Bank Digital Currencies are a form of digital public money—issued directly by central banks. As they represent a liability of the central bank, therefore they constitute a risk-free settlement asset and play a foundational role in anchoring monetary and financial stability. CBDCs may be designed for use exclusively by financial institutions, corporates, and other entities operating in wholesale financial markets (wholesale CBDCs), or made accessible to the general public (retail CBDCs). Stablecoins are privately issued digital units of value designed to maintain a stable value relative to a reference asset—typically a fiat currency (e.g., USD), a basket of currencies, commodities, other crypto-assets, or make use of algorithms for that purpose[4]. Stablecoins are widely used in crypto-asset markets and decentralized finance (DeFi) for trading, settlement, and liquidity purposes, and in some jurisdictions may be regulated when used for payments. |

2. Wholesale payments: CBDCs still the safest settlement asset, yet big players aim to attract more volumes

2.1 CBDCs are still seen as the ultimate settlement asset, enabling complementarity with stablecoins

With the tokenization of finance, CBDCs are increasingly seen as paramount to provide a safe settlement asset. Central bank money is indeed the single most liquid asset which eliminates both credit and counterparty risks. Whether in its current digital form or in a tokenized form, as a CBDC, it can ensure that digital transactions are settled safely. The IMFS thus ultimately relies on central bank money settlement, and nearly all financial players will probably continue to rely on it too to settle large value transactions.

At the other end of the spectrum, the current volume of stablecoins remain very small[5], compared with the total amount of money issued, and they are very little used to settle large value payments. Such payments entail important capital expenditures to guarantee resilient infrastructures as well as full trust in the issuer of the settlement asset. However, some countries have offered or are considering offering access to central bank money for stablecoins issuers[6], usually non-bank payments service providers. Stablecoins could in this fashion offer useful use-cases (e.g. cash management for large corporates) while ultimately being settled in central bank money.

Moreover, when offered on a unified ledger, CBDCs would always ensure safe settlement, while benefiting from key benefits of Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), such as programmability of payments and composability of assets. CBDCs could also be provided and operated on a fundamental layer (so-called “layer 1”), where stablecoins from different ledgers could circulate, thus reducing potential fragmentation and enhancing interoperability. Finally, the coexistence of stablecoins and tokenized assets (e.g. deposits) could be ensured and secured with a CBDC on a single ledger, enhancing liquidity and efficiency.

2.2 Growing volumes and use-cases of stablecoins could entail greater competition with central bank money in the long run

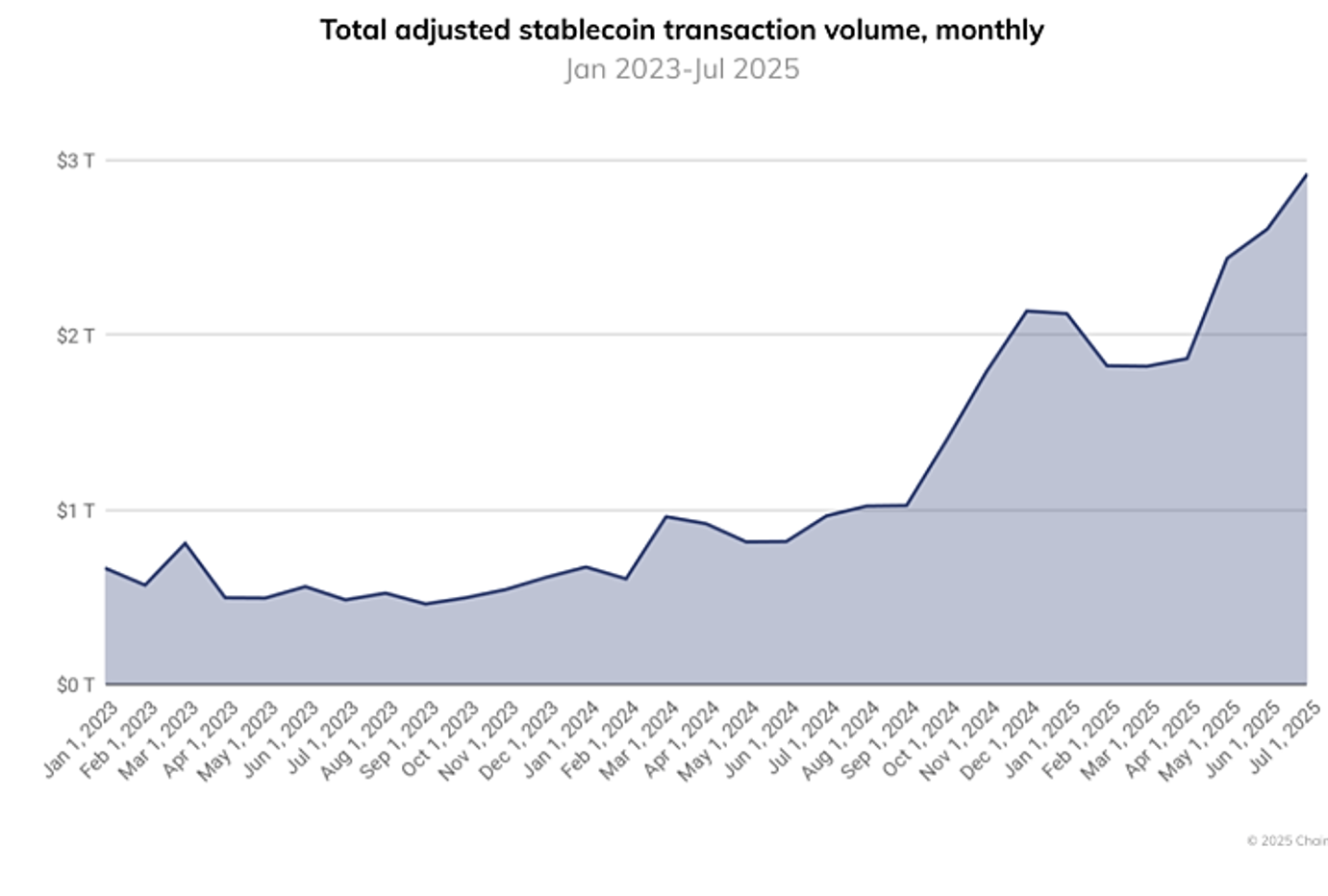

Growing volumes of stablecoins (see chart below) could have a material impact on global financial stability if they are not ultimately settled in central bank money. Private issuers would have to handle the settlement of large-value payments. Arguably, smart contracts and atomic settlement should reduce settlement risk. However, counterparty risk would be transferred towards the stablecoins issuers, who should be able to redeem stablecoins at all times. Stablecoins issuers would also not benefit from the same amount of trust as central banks.

Competing with (tokenized) central bank money would mean financial institutions and corporations prefer making large-value payments with stablecoins rather than with fiat currencies. Such payments should be backed by assets, usually held at financial institutions, but only stablecoins would circulate freely[7]. This would mean a potential privatization of money, where different currency issuers would coexist, and the market would help select the best ones, as envisioned in Hayek’s Denationalisation of Money[8]. This shift of significant volumes from fiat to stablecoins would need to be underpinned by privately operated systems that handle transactions, reconciliation, liquidity, FX risk, etc. Several companies already manage most of these functions, but it is unlikely policy makers would let such infrastructures grow significantly without oversight giving the risks for global financial stability, as the Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS) example showed[9].

However, big corporates might find it useful to use stablecoins to streamline liquidity management, thereby circumventing the current correspondent banking system and, by extension, the two-tier reserves systems. This would possibly bring along competition with CBDCs to attract business. Nevertheless, this risk should not be overestimated for wholesale payments, as central bank money is still the only risk-free asset available to settle transactions.

3. Retail Payments: Complementarity is possible, yet competition remains strong

3.1 CBDCs and stablecoins as complementary solutions for closing retail payment gaps

In the retail payment landscape, both CBDCs and stablecoins aim to make digital transactions faster, cheaper, safer and more inclusive — but they approach the goal from different foundations. When well-designed, they can complement each other by broadening consumer choice and encouraging innovation within a safe regulatory perimeter.

Retail CBDCs, issued directly or indirectly by central banks, serve as public digital money—a digital equivalent of cash. They are backed by the full faith of the central banks/ monetary authorities ensuring trust, stability, and finality of settlement. Their main policy objectives are to preserve monetary sovereignty, promote financial inclusion, and provide a secure anchor for the digital economy.

Stablecoins have become increasingly prominent in environments where central banks have not yet introduced fully fledged digital retail solutions. Their adoption is particularly strong across cross-platform ecosystems such as decentralized finance (DeFi), crypto exchanges, online trading platforms and various remittance channels, where users value seamless interoperability across different services. For participants already active in digital asset markets, stablecoins offer rapid settlement, continuous global accessibility and ease of integration with a wide range of digital applications. These features fill gaps in functionality and make them a practical complement to the regulatory certainty, institutional backing and operational reliability associated with CBDCs.

If interoperable frameworks and sound oversight mechanisms are established, stablecoins could act as innovative front-ends while CBDCs remain the trusted backbone. For example, a CBDC system could allow licensed stablecoin issuers to build payment interfaces or programmable features on top of central bank infrastructure. This “two-tier” structure would enable competition and product diversity while preserving systemic stability.

In jurisdictions with advanced payment systems, such as the EU, UK, and parts of Asia, such complementarities could help integrate retail digital money into everyday transactions — from e-commerce to peer-to-peer transfers — without fragmenting monetary trust.

3.2 Yet rising stablecoin adoption may intensify competition for users and payment flows

However, in practice, CBDCs and stablecoins often compete for the same space: digital payments and store-of-value functions for the public. The tension arises from who provides digital money and whose liability it represents.

Stablecoins are typically liabilities of private issuers. Their promise of maintaining a 1:1 peg to fiat currency depends on the quality, liquidity, and transparency of reserve assets. While some, like USDC, hold high-quality reserves[10], others have faced scrutiny over collateral composition and redemption guarantees. For example, Tether’s reserves have historically included not just cash and short-term Treasury equivalents, but also corporate bonds, secured loans, precious metals, and even crypto. S&P Global’s analysis noted around 15% of its reserves are in such riskier assets[11]. This raises concerns about financial stability and consumer protection, particularly if a stablecoin grows large enough to affect the payment ecosystem or money supply.

Retail CBDCs, if widely adopted, could displace stablecoins by offering similar digital functionality but with central bank credibility and zero credit risk. Yet such displacement could also limit private sector innovation, reducing diversity in payment options and slowing the pace of new use cases like programmable payments or cross-platform settlement.

In emerging markets, competition may focus on trust and accessibility. Stablecoins, often linked to global platforms or dollar-based ecosystems, can be attractive for users seeking price stability or cross-border reach. CBDCs, on the other hand, aim to strengthen local currency usage and domestic financial inclusion.

| Box No. 2 : The Eurosystem Approach to Tokenization of Finance To foster the benefits of innovation while safeguarding financial stability and monetary sovereignty through central bank money as the anchor of the tokenized world, the Eurosystem developed a three-layered approach regarding the tokenization of finance: First, the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) covers the issuance and provision of services on crypto-assets, including on tokens backed by the euro or other assets. Second, the Eurosystem is developing two projects, Pontes and Appia. The former aims to bridge the gap between legacy infrastructures and DLT by offering a Eurosystem DLT-based solution. The latter seeks to provide an innovative and integrated payments and securities ecosystem in Europe, by exploring solutions such as a European shared ledger or a network of interoperable platforms. Finally, the Eurosystem aims to be ready to issue a digital euro, not directly but through commercial banks (retail CBDC) by the end of the current decade. This approach provides a solid foundation for the development of innovations such as stablecoins, potentially backed by the Euro, to harness the full benefits of complementarity. |

4. Conclusion: Policy Discussion

The rise of CBDCs and stablecoins underscores a fundamental transformation in money: the digitalization of trust. Both forms of digital currency seek to enhance efficiency, resilience, and inclusion, yet they differ in governance, risk, and accountability.

From a policy perspective, the challenge is not to pick a winner, but, as it is today in the traditional financial system, to design coexistence that preserves monetary sovereignty while harnessing private-sector innovation. Clear legal definitions, prudential requirements, and interoperability standards are essential to avoid fragmentation and regulatory arbitrage. Stablecoin issuers should be subject to transparent reserve management, redemption rights, and operational resilience requirements—especially if their tokens are used widely for payments.

Central banks, meanwhile, must ensure that CBDC design choices—such as privacy levels, distribution models, and offline capabilities—support public confidence and financial inclusion without crowding out private innovation and commercial banks. Without careful oversight, a few dominant private issuers could gain disproportionate influence over digital payments, raising concerns about concentration, data control, and anti-competitive behaviours.

Conversely, a CBDC that becomes overly attractive relative to bank deposits or private payment instruments could unintentionally accelerate disintermediation, reshaping the funding model of commercial banks. Policies must therefore balance innovation with safeguards, ensuring diverse, competitive payment options while preserving the stability of the financial system. Collaboration between regulators, central banks, and FinTechs is key to achieving balance.

On a global level, interoperability among CBDCs and regulated stablecoins could reduce cross-border friction, enabling faster, cheaper, and more transparent international transactions. The goal should be a plural but harmonized ecosystem, where public and private forms of digital money reinforce—rather than replace—each other.

The coexistence between CBDCs and stablecoins finally hinges upon the geopolitical landscape. Some jurisdictions (e.g. the US) favour stablecoins, which might lead to competition with other jurisdictions developing CBDCs (e.g. Europe, China). Besides technology, willingness to maintain or transform the current ranking of international currencies may also impact how stablecoins and CBDCs interact. One of the possible outcomes could be a “digital dollarisation” of the IMFS, whereby dollar-backed stablecoins are used globally as means of payment, undermining monetary sovereignty of other jurisdictions. International cooperation is thus needed to ensure stablecoins and CBDCs complement each other to provide efficient and secure payments.

The ultimate question is whether coexistence is feasible without undermining the stability of the monetary system. For coexistence to work, regulators must establish clear boundaries: stablecoins can operate as innovative complements within a framework anchored by public money, while CBDCs guarantee the ultimate unit of account and settlement finality.

“In this vision, CBDCs provide the anchor of trust, while well-regulated stablecoins bring agility and innovation. Together, they can redefine how value moves across borders and across platforms — not as rivals, but as partners in the evolution of money.”

[1] Currently, “137 countries & currency unions, representing 98% of global GDP, are exploring a CBDC. In May 2020 that number was only 35.” Cf. Central Bank Digital Currency Tracker – Atlantic Council [consulted on 17/10/2025]

[2] For the latest developments, see G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-border Payments: Consolidated progress report for 2025.

[3] Text – S.1582 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): GENIUS Act | Congress.gov | Library of Congress

[4] See Stablecoins on the rise: still small in the euro area, but spillover risks loom, ECB, 2025.

[5] Around USD 280 billion (see ECB, 2025, ibid.), compared to USD 194 trillion in cross-border payments. For a more complete picture, see The 2025 Global Adoption Index: India and the United States Lead Cryptocurrency Adoption

[6] See for example Embracing New Technologies and Players in Payments, C. J. Waller, October 2025.

[7] However, most regulation require a 100% reserve backing (e.g. 1USDC = 1 USD), meaning stablecoins lack elasticity and scalability.

[8] Hayek, F. (1976). Denationalisation of Money. An Analysis of the Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies, The Institute of Economic Affairs.

[9] See for example CLS – purpose, concept and implications, 2003, ECB Monthly Bulletin, January.

[10] According to Circle (the issuer of USDC), most of its reserves are held in “highly liquid cash and cash-equivalent assets. S&P Global gave USDC an asset assessment score of 1 (“Very strong”).

[11] Tether’s Ability To Maintain Dollar Peg ‘Constrained’ Says S&P Global